Ostara falls on March 20th this year and after the pre-emptive celebrations of Imbolc, the date of the vernal equinox means that spring is finally, and officially, upon us. The celebration of Ostara is a significant event on the Wheel of the Year but it is not the only way to celebrate this time of the year.

The vernal equinox, is one of two points in the year when there is an equal amount of day and night. From this day until the summer solstice, which is the longest day, the length of days increase. After the solstice, they begin to shorten. However, a word about this timing. These dates are accurate for the northern hemisphere only. The southern hemisphere experiences the opposite and this time of year is actually the autumnal equinox for people down south.

We’ve covered Ostara quite extensively on Spiral Nature from discussing why we dye eggs to some delicious recipes to celebrate the season, but the way traditionally celebrate Ostara in the west isn’t the only tradition that exists in the world. The vernal equinox happens for everyone and as such, it’s celebrated by everyone.

Our focus in the west — for the most part — is seeing the vernal equinox as a fertility festival, in which we honour the world as it’s coming back to life and this theme is carried throughout many celebrations, however, this is not the only way to celebrate this day.

Pancakes and bonfires

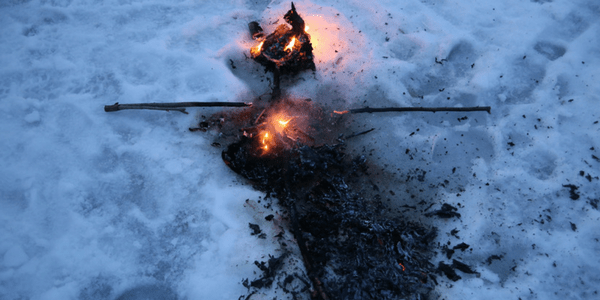

Maslenitsa is a Eastern Slavic folk holiday that was originally celebrated by sun worshippers and marked the end of winter and coming spring.1. This festival reminds people of Mardi Gras because of its wild celebrations and heavy food choices. Blinis are the celebratory food of choice, a Russian-style pancake, usually topped with other things, and meant to resemble the returning sun.

Although this festival can get very rowdy with fist fights and bears (yes, bears) there’s still a very ritualistic aspect to it. At the end of the three-day long celebration, people will ask forgiveness from their neighbours, quite possibly for the bears but more likely in a general sense, then burn the “Lady Maslenitsa,” a straw effigy that represents winter. In earlier times, the left-over blinis were burned as well and the ashes were spread over the ground to help nourish the new crops for the coming year. The burning of this effigy signified the literal heat of the sun that melts ice and moves into the warming season.

This celebration has the same festive spirit of the Ostara beliefs but due to the climate, the practice is closer to those that we see during Imbolc with the inclusion of fire and the melting and burning away of the cold winter. There’s also less of a focus on fertility and it is more about celebrating the physical return of the sun and warm weather, for what it is.

This is an interesting festival because it has been tied to the Catholic church2 in more recent history but, it comes as no surprise that this doesn’t take away from it’s Pagan roots. Because of it’s religious ties, the timing of the celebration moves yearly. Still, given that it has it’s roots in a decidedly not Catholic practice, it is an interesting study of the ways that old traditions are absorbed into the popular religions seamlessly.

Festival of Isis and the Nile begins to rise

The people of Kemet (what is now known as Egypt) were meticulous time keepers and astrologers so it makes sense that they would have a festival during this time but because their climate, we don’t see a lot of the same motifs that we see in the west. There is still the same focus on fertility as this coincides when the Nile begins to rise again bringing life to the desert, however, it goes much deeper than that.

During this time fertility was celebrated as the rising banks of the Nile meant that life-giving soil would be deposited for the growing season and life in what is otherwise a desert would be able to continue for another year. As such, it was also a time of harvest. Prior to this, the growing season would be ending and the crops gathered to make way for the coming water. Well, more accurately speaking, this was to save the crops from the floods because the water was coming no matter what!

Due to the timing of the flooding of the Nile River, the spring is when the harvest took place which is very different than the western understandings of spring, which is a planting and growing season. One of the many hats that Isis wears is that of a harvest goddess and the legend, according to one source,3 is that it was her tears over the loss of her husband, Osiris, represented by the harvested crops, that caused the Nile to flood.

This alignment with the harvest season puts an interesting spin on the season and reminds that some things cannot begin until other things end. The crops must be harvested so that there is room to plant, the Nile must flood to revive the earth.

A visit with the ancestors

In Japan, the vernal equinox is called Shunbun no hi and is celebrated as part of a larger, seven-day tradition known as Haru no higan. Although the exact origins of this celebration are unknown, it has been in practice by the people of Japan since the eighth century.4

This day is spent tending to the graves of ancestors and helping their spirits cross over and reach enlightenment, in accordance with Buddhist beliefs. This includes praying, weeding and washing graves, as well as leaving flowers and burning incense. Small food offerings are also left at graveside for them.

This celebration seems to suggest that the veil between worlds is thinner at this time, thus why it is an ideal time for helping so souls to the afterlife. This sort of belief, in the west, is generally honoured most at Samhain; however, equal amounts of light and darkness at the equinox also make it an ideal time for threshold crossing. The acts of tending the graves helps the spirits find their way and, perhaps, can calm any anxiety because they’ll see their loved ones still care for and remember them.

This is the direct opposite of how the west celebrates the equinox which is usually considered as a life-affirming time. The focus the past may seem strange but much like the Egyptian belief that recalls the passing of Osiris, we are reminded that life is a cycle and we must respect all parts of it.

Spring cleaning and the New Year

The festival of Nowruz (No-Rooz) is celebrated in Iran as the New Year and has also been called the Persian New Year. Its roots are based in the Zoroastrian tradition but is still celebrated today as a secular holiday much like the commercial aspects of Easter, for many people. In fact, the celebration of it has spread through the Middle East and Asia making this a diverse feast day for a variety of people.5

Instead of eggs and bunnies (and the not so subtle fertility imagery therein), this festival is about purification, renewal and fresh beginnings. Although there is a feast, it seems as though this aspect is more “modern” and not found in any of the original texts.6. People spend time cleaning the home and releasing the energies of the past year. This festival does incorporate some fire as a cleansing tool and celebrants may jump over small fires to purify themselves for the new year. The main belief is that there is both good and bad in the world and that we should strive for the good. This day has become a sort of nonsecular day in many places but there’s still a great deal of political tensions that surround it.

It is not an Islamic holiday, and it’s Zoriastrian roots put it at opposition with some governments throughout history but today most allow it’s celebration. For Kurdish people in particular, it has become a political celebration that speaks out against their oppression by the Turkish government.7

It’s interesting to conceive of the new year as starting at a time when all things are equal and we are moving into a time of brighter possibilities.

The world is diverse and so is tradition

Our focus during Ostara in the west tends to be heavily on the idea of new beginnings. We speak of fertility and new growth, new energy but looking at celebrations from the rest of the world we can easily see the ways that differences in culture and climate affect our celebrations.

The main theme of the vernal equinox is that the world is changing from one state to another. There is a sense of renewal and rebirth but these concepts do not always have to be attached to fertility, as we tend to do in the west. There are many ways to celebrate this special time of the year.

Image credits: Patrizia lyap, LM TP, and Kyle Pearce

- Maria Godoy, “It’s Russian Mardi Gras: Time For Pancakes, Butter And Fistfights,” NPR, 2017. [↩]

- Russian Survey, “Maslenitsa Celebrations,” 2017. [↩]

- Sir James George Frazer, The Golden Bough (Macmillan Reference, 1922). [↩]

- Shane Sakata, “Celebrating Shunbun No Hi In Japan,” Nihonsun, 2017. [↩]

- Iran Chamber, “Culture Of Iran: No-Rooz, The Iranian New Year At Present Times,” 2017. [↩]

- April Fulton, and Davar Ardalan, “Nowruz: Persian New Year’s Table Celebrates Spring Deliciously,” NPR, 2017. [↩]

- Euphrates Institute, “Celebrating Nowruz: Cultural Traditions, Politics and Peace,” 2017. [↩]