The Book of Oberon: A Sourcebook of Elizabethan Magic, by Daniel Harms, James R. Clark, and Joseph Peterson

The Book of Oberon: A Sourcebook of Elizabethan Magic, by Daniel Harms, James R. Clark, and Joseph Peterson

Llewellyn Worldwide, 978-0-7387-4334-9, 585 pp. (including bibliography and index) 2015

The Book of Oberon is a reprint of a late 16th century grimoire — a manuscript in the Folger Shakespeare Library — and is an excellent resource for understanding the development of ritual magick as well as investigating literary, religious, and cultural questions in Elizabethan England.

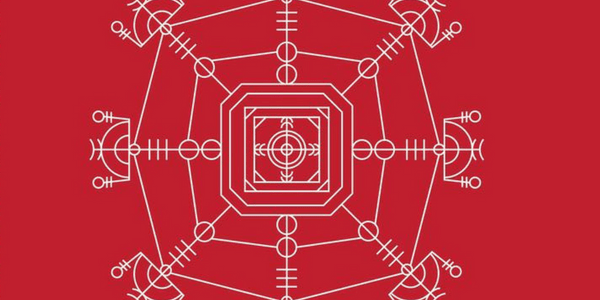

Given that the original manuscript was written in secretary hand (and by several different hands), this contemporary edition makes an obscure text much more accessible. The editors have slightly modernized the renaissance English (by expanding abbreviations, normalizing punctuation and capitalization, etc.), and their English translations of the Latin passages are placed side-by-side with transcriptions of the Latin. The book itself is very pretty; under the dust jacket is a gilt-lettered cloth hardback binding and marbled endpapers. Throughout the text, red lettering mirrors red ink in the original manuscript, highlighting holy names and other important words. There are also a large number of illustrations in red and black, such as drawings of spirits, angels, circles, sigils, talismans, glyphs (like anchors), and decorative snakes.

Early in the introduction, a footnote directs readers to the online version of the manuscript posted by the Folger Shakespeare Library, so they can easily compare this book with the primary source. The manuscript was most likely composed between 1575 and 1583: a decade before A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare’s famous text about the fairy king Oberon, was first performed.

The Book of Oberon is well cited, encouraging the reader to expand their research beyond this one (very heavy) volume. The citations indicate what source material is copied — like The Lesser Key of Solomon, old prayer books, or biblical chapters and verses — as well as reproduce marginalia from the original manuscript, reference modern sources, and define archaic terms.

The editors explain that the manuscript is a “magical miscellany, a compilation of material gathered by a magician or magicians over time as needs or opportunities presented themselves and with little effort made at overall organization or systematic labelling of the texts.”1 While typical of a working magician, this was vastly different from the printed miscellanies of the period, such as Tottel’s Miscellany from 1557 — a poetry anthology that helped popularize the sonnet in England by including Thomas Wyatt’s English translations of Petrarch’s sonnets. Tottel spent a great deal of effort on arranging and titling his selections as well as regularizing Wyatt’s meter to show that the English tongue was as poetic as Italian.

The haphazard structure of The Book of Oberon can help the reader construct a biography of the magician(s) who created it. Patterns of behaviour, cultural concerns, and access to older grimoires can be discerned from the disorganization. Like most magicians, the author(s) of this renaissance grimoire copied from a variety of existing magical and Biblical texts, such as Arbatel, the Sepher Raziel, and the Enchiridion of Pope Leo III, as well as the Vulgate Latin Bible or the Great Bible of 1539-1569.2

The workings in The Book of Oberon fall into three familiar categories: wealth, health, and love. There are spells for discovering treasure and discovering thieves; for invisibility; for headaches, toothaches, and conception; and to defeat enemies and win friends. A large number of pages — perhaps the majority of the pages — are devoted to conjurations of spirits, including the titular Oberon (or “Oberyon”).3 My favourite working is conjuring spirits to make and write books; “thou Abrinno or Obymero, per noctes [‘every night’], symon mobris, Laycon, Catys, Oropys, and drypys, you angels being the best writers, now do you here appear, and that in the shape of writers […] make me such a book incontinent containing this form and to write the same.”4

The spirits conjured in The Book of Oberon include angels and even Satan and rely heavily on holy names and Biblical passages or allusions. Personally, I don’t work with the Abrahamic god or his pantheon of saints, angels, and demons, but I find researching grimoires with heavy Christian influences useful for understanding the structure of spells. This text is filled with many examples of repetition and speaks to the power of naming and stories. For instance, spirits are conjured and bound by “the holy names of God + Degeron + or + Gegeron + by the which Moses bound the Red Sea that it stood as still as stone on both sides like a wall while the people of Israel passed through.”5 This pattern is also seen in sermons of the period (and today); power is derived from the addition of various names with storytelling. Occultists who work with different gods or energies can choose to mimic (or reject) these patterns with different names and stories.

Furthermore, the repeated use of the Abrahamic pantheon and mythology can help shed light on religious and literary questions of the Renaissance. Scholars from several different disciplines — such as history, literature, and cultural studies — could use this book in their research. For example, The Book of Oberon would be an excellent source to use in a paper about Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. Faustus, in his deal with the devil, is forbidden from mentioning the biblical stories that are supposed to conjure and bind spirits in many grimoires. Did Marlowe not read miscellanies written by magicians? Was Faustus an unskilled magician who failed to control the spirits he conjured?

The Book of Oberon’s editors use footnotes to place their chosen manuscript in “the broader tradition of western ceremonial magic.”6 One interesting example in Part Two of the book is a footnote that indicates a passage is the “earliest known practitioner’s account of the magical amulet called the toad-bone,” and references a modern study on the amulet.7 The passage includes very specific directions for obtaining the bone of a frog, and explains that a ring with the frog-bone can be placed on the right hand of “any woman” the magician desires, and she will fall in love with the toad-bone harvester.8 Another bone harvested at the same time from the same frog will repel the “woman.”9

However, the editors may not condone trying out this amulet because it involves killing a frog. They mention that they “strongly condemn mistreating animals”10 in both footnotes and the introduction. As someone who does not kill animals in her magical practice, I think these kinds of spells are worth reading because they help me learn more about the traditions of magick as well as the culture of Elizabethan England.

In addition to tracing the toad-bone amulet’s recorded history, this section of the grimoire is fascinating in terms of studying courtship. The toad-bone “love experiment” is placed between a ritual for hunting and a spell for shooting arrows.11 This positioning could be determined by the magician’s “needs or opportunities,”12 and offers many avenues for investigation — the courtly love tradition dating back to the medieval era associates hunting and archery (as well as other violence) with wooing women, and magick is a key element in many chivalric tales.

The Book of Oberon is a great book for anyone who wants to learn about western ceremonial magick or about the English Renaissance. It is a solid starting point for researchers from a variety of disciplines, offering insights into written language, sigils, gender roles, the Protestant Reformation, psalm translations, the theatre, and much more.

- p. 6 [↩]

- p. 27-28 [↩]

- p. 207, 454 [↩]

- p. 235 [↩]

- p. 126 [↩]

- p. 29 [↩]

- Footnote no. 808, p. 501 [↩]

- p. 501 [↩]

- ibid. [↩]

- Footnote no. 105, p. 114 [↩]

- p. 500-501 [↩]

- p. 6 [↩]