Spellbound: Magic, Ritual and Witchcraft Exhibition Catalogue, by Sophie Page, Marina Wallace, Owen Davies, Malcolm Gaskill, Ceri Houlbrook

Ashmolean Museum Publications, 978-1910807248, 176 pp., 2018

Described by some reviewers as “mesmerizing,” “irresistibly creepy,” and “bewitching,” according to its dedicated website, the Ashmolean Museum’s exhibition Spellbound: Magic, Ritual and Witchcraft didn’t live up to those expectations. Instead, the exhibition was a disappointing muddle. It was set out in such a way that some artifacts and information were impossible to see between crowds of visitors and “atmospheric” dim lighting intended to evoke a pseudo-spooky atmosphere. However, its accompanying catalogue is well worth investing in.

The Spellbound catalogue is a substantial work in itself, rather than just a descriptive inventory of the exhibition artifacts. It is substantially illustrated throughout and contains a collection of essays that delve into the nature and history of magical thinking. It starts by explaining medieval conceptions of magick and how these beliefs affected the lives of our ancestors, and ends with an analysis of modern day ritualistic behaviour. A central theme running throughout this work is the innate human proclivity for ascribing beneficent or malevolent powers to certain objects or processes.

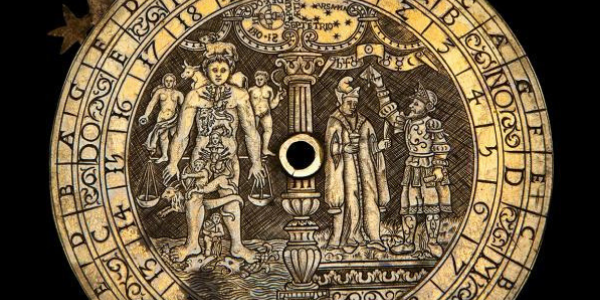

The complex structure of the medieval cosmos and its direct effect on the health and fortune of every individual is discussed in Sophie Page’s essay, complete with several illustrations showing diagrammatic manuscripts bearing a dizzying array of symbolic correspondences intended to explain how “microcosmic man” is directly influenced by the celestial spheres above him.

An intriguing aspect of a belief in such cosmological intervention was how Europeans of the Middle Ages squared this notion with their Christian faith. The answer to this, as far as the Church authorities were concerned, seems to have been a sliding scale of tolerance. At one end, they hazily equated the idea of a universe brim-full of spiritual entities with the ongoing battle between biblically-endorsed angels and demons, whilst at the other they condemned practitioners of magick who propagated their craft in ways that seemed to fundamentally circumvent the Christian worldview.

As important as such metaphysical considerations are for understanding the context in which magical thinking took place, the sections of the catalogue devoted to providing written and visual testimony of this in practice, particularly in terms of the home as a place for promoting domestic well-being, are among the most intriguing. Depending on one’s beliefs (spiritual or otherwise), maintaining that well-being can rely on a number of often quite idiosyncratic factors that can veer into what might be deemed by some as ritual or superstition. This propensity to keep malignancy from the door via the use of various apotropaic artifacts has been a consistent human trait. Spellbound provided several intriguing instances of this. Many of the objects presented had been recovered from places around the home where they had long been concealed in order to ward off evil. Numerous witch bottles were on show, their contents often a gruesome assortment of human fluids and animal viscera, all intended to prove a potent cocktail fit to repel the beldam next door.

Not that it was always about thwarting witches. As now, the natural world could pose a threat to household contentment. During the medieval and early modern periods, the threat of lightning setting the house on fire could be averted by placing so-called thunderstones — usually prehistoric stone axes — in the rafters, whilst the mummified remains of a cat and a rat found side by side in a domestic wall space told its own story about using sympathetic magick in the service of vermin control. Not all the household objects presented or discussed could be securely confirmed as having served a particular purpose, so for every witch bottle found, the significance of why other objects were deposited — such as clothing, shoes, and household items — remains unresolved; a timely corrective to any perceived assumptions about how much the modern world comprehensively understands the motivations of our ancestors.

Perhaps inevitably, given the thematic impetus behind Spellbound, the figure of the witch in her early modern guise could not just be confined to a cameo part in the history of talismanic household objects. That said, the section of the catalogue wholly devoted to the “fear and loathing of witches” as the chapter title has it, feels, at times, like a mandatory jog through some very familiar and much referenced texts. Even so, its author, Malcolm Gaskill, provides a salutary reminder that back in the 16th century “people were less blindly lost in superstitious darkness than they are often thought to be,” and that if there was a consensus about the reality of such matters, “it was because, as with our own rational outlook, demonology made sense.”

Alongside the text there are many illustrations, prints, and paintings that serve to reinforce just what it was that made the subject of witchcraft so intriguing, terrifying and, it has to be said, not infrequently titillating for its audience. The reasons behind all this have been meticulously analysed and explained in numerous studies over the years, and there is nothing new to be said in this present account. Even so, the figure of the witch cavorting with the devil or balefully stirring her cauldron remains a staple of popular occult imagination and will no doubt always remain so.

Aside from a final section dealing with the various art installations that punctuated the exhibition itself and which had to be witnessed at first hand to be truly judged on their own merits, the catalogue ends with a consideration of rituals and magical thinking in the modern world. Although the claim is that “many people assume that magical thinking in Western culture is a feature of the past; that the popular beliefs and ritual practices explored in this exhibition belong to their ancestors rather than themselves,” this surely doesn’t pay enough regard to those of various religious and spiritual persuasions who accept and positively cultivate magical thinking in all its many guises as part of their daily lives.

It undoubtedly is the case that those who knock on wood or send good luck cards are practicing a form of magical thinking, even though they may not recognize it as such. The catalogue also cites the rise in popularity of attaching love locks to bridges as being another practice the atavistic provenance of which will probably not be apparent to those who take part in it.

Well, maybe, but to end in this manner with only a perfunctory nod to those who, for instance, tie rags to the Glastonbury Thorn as an example of fully conscious ritualistic behaviour seems to smack of the triumph of common sense modernity over those quaint beliefs which only a marginalized few obstinately believe in.

All in all, Spellbound succeeds in its aims as a concise and well-presented overview of “magic, ritual and witchcraft.” There is plenty in the catalogue to appeal to those with varied levels of interest in and knowledge of these subjects. The essays are thought-provoking and engaging, and the many illustrations of the artifacts that were on show are, unlike in the exhibition itself, readily accessible and able to be properly seen — without a hint of pseudo-spooky atmosphere.

Image credits: Ashmolean Museum