You likely have at least a passing familiarity with the Cthulhu Mythos. The image of a gigantic many-tentacled monstrosity pouring through a hole in space-time has, in the span of a few decades, risen from obscure out-of-print pulp fiction to become nearly archetypal. Yet I find that much of what has been written about the Cthulhu Mythos in a magical or spiritual context has been limited, not reflecting what I understand as their most important aspects. These entities take many forms and mean many different things depending on who you ask. But whether you see them as primal forces of chaos and change, atavistic holdovers from a previous universe, aliens that exist in four or more dimensions, or embodiments of the nightmares of conservative white men, working with them has its unique rewards and can be powerfully transformative.

You likely have at least a passing familiarity with the Cthulhu Mythos. The image of a gigantic many-tentacled monstrosity pouring through a hole in space-time has, in the span of a few decades, risen from obscure out-of-print pulp fiction to become nearly archetypal. Yet I find that much of what has been written about the Cthulhu Mythos in a magical or spiritual context has been limited, not reflecting what I understand as their most important aspects. These entities take many forms and mean many different things depending on who you ask. But whether you see them as primal forces of chaos and change, atavistic holdovers from a previous universe, aliens that exist in four or more dimensions, or embodiments of the nightmares of conservative white men, working with them has its unique rewards and can be powerfully transformative.

Their history (on Earth, at least)

The best place to start is in the early 20th century, with a then-unknown horror writer named H.P. Lovecraft.1 He is considered the inventor of the cosmic horror genre, based on the idea that the universe is incomprehensible and ultimately indifferent to human efforts. His writing portrayed a hostile universe, filled with massive, unknowable beings who cause wanton chaos and destruction — a portrayal which drew both from his existential fears and his reactionary fears as a racist xenophobe.

There’s some debate about how conscious Lovecraft was of the energies he was working with, and how much experience he had with the occult. He was certainly aware of it, in the way that many horror writers are, but there’s nothing to suggest he was a magician. Personally, I think he did make some sort of contact (likely through the night terrors that inspired much of his work), but he was too caught up in his own fear and bigotry to see anything but horror in it. But for all his flaws, he wrote some innovative and evocative fiction that, while commercially unsuccessful, drew the attention of several artists and writers. Perhaps recognizing some underlying truth, they wrote new stories about Lovecraft’s creatures and ideas, which coalesced into a shared universe which became known as the Cthulhu Mythos.

A familiar unknown

Many witches and magicians who work with the Cthulhu Mythos prefer to ignore its conservative origins and take an apolitical approach, but I think keeping them in mind creates a strange opportunity for self-acceptance. Lovecraft’s beliefs affected every part of his writing. These entities’ forms often echo marginalized human bodies, spliced with whatever animal a particular author is afraid of. (Why tentacles? Because Lovecraft was terrified of pretty much all sea life.)2

As a mentally ill person, I’m intrigued by Lovecraft’s often bizarre ideas about insanity. He was terrified of it, both from a family history of mental illness and a reactionary fear of (non-western, non-empirical ways of being3 (something witches are very familiar with). Lovecraft seemed to think sanity worked like an on and off switch, with any glimpse into the realities of the universe flipping it permanently into the “off” position. To him, seeing the truth meant insanity. That sounds like an insanity I can get behind. These beings encourage madness, that is to say they value unusual ideas and atypical ways of thinking. I find I work with them best when I allow my brain to function as it wants to function and trust my own unique perspective.

This, to me, is a vital part of working with the Cthulhu Mythos: celebrating the parts of yourself that conservative, reactionary people like Lovecraft see as ugly and irrational and monstrous, as threats to their social order and their peace of mind. Some call it “living in your truth” but I prefer “spreading your madness.”

Working with the Cthulhu Mythos

Given how steeped the Cthulhu Mythos is in modern fiction, you’re probably wondering if these entities are real, and if so, what exactly they are. I do think they’re real, in the sense that entities exist that bear a close resemblance to those the Cthulhu Mythos writers described. The names, descriptions, and other specific details given in stories probably aren’t correct, but they respond to them and they’re convenient shorthand to communicate with them. There’s also some give and take in how they manifest themselves; sometimes they take the “amorphous mass of tentacles” form they’ve been assigned if they want to be recognized, and sometimes they’ll choose something completely different to drive home how alien they are.

As for what they are, the possibilities I mentioned in the first paragraph are all part of the truth. However, I reject Lovecraft’s nihilism and prefer to take a more absurdist approach; a little disorder is often just what’s needed. I’ve worked with them for years now, and much of what I’ve learned is difficult to put into words. I can only summarize what I know of them: They like chaos, magick (and chaos magick) and innovation and dislike stagnation and closed-mindedness. Some spread chaos and new ideas, some hoard and share knowledge. Some seem to function like bacteria, decomposing old, dead parts of the universe, while others are more like classic, such as psychopomps. They’ve helped me quite a bit in my magical efforts since 45’s (American President Donald Trump) election, and they can be a valuable part of an anti-oppressive practice. However, they can also be unpredictable and destructive, and can have a draining, overwhelming effect on your energy and mental state. Even if they do take a shine to you and decide to help you, their definition of “help” may not match yours. I recommend starting small and working with one entity for a little while until you know how they might affect you.

While it’s beneficial to be familiar with the more well-known Cthulhu Mythos stories and the style and ideologies of the various authors, I’ve had better results with an intuitive, free form approach than in trying to replicate what’s been written. There is a temptation to get sucked into the “nerd details” of the Cthulhu Mythos, such as the relative power levels of each entity, and how they are related to each other — later Cthulhu Mythos authors created a complex and often contradictory family tree — but I find they keep the conscious mind too active and discourage genuine experience.

Likewise, many people will argue over specific pronunciations of words and names, but that isn’t important either. The names given in stories are only approximations of sounds unpronounceable to human tongues. It’s much more important to get into the spirit of the Cthulhu Mythos; try to sound like you’re descending faster than light from a gap between the stars toward the earth, or perhaps crawling out of the ocean coughing up primordial ooze, and you’ll have much more success than if you try to imitate someone else’s pronunciation.

Below are some of the entities most commonly worked with by magicians. I have added my thoughts on and experience with them. Keep in mind that there are many others you could encounter. There are easily hundreds of unique beings described by Cthulhu Mythos authors, and there’s always the possibility of meeting something completely new.

Azathoth

Outside the ordered universe is that amorphous blight of nethermost confusion which blasphemes and bubbles at the center of all infinity — the boundless daemon sultan Azathoth.4

There’s honestly very little to be said about the creator figure in the Cthulhu Mythos. Most often called The Blind Idiot God (but I prefer The Nuclear Chaos), Azathoth is said to be sleeping at the centre of all existence, waking only at the end of the universe. Its messenger, Nyarlathotep, attends to it in its sleep and interprets its babbling. I typically conceptualize it as less of a being and more of a force. Whatever it is, it’s not responsive and there’s not much point to working with it.

Yog-Sothoth

Yog-Sothoth knows the gate. Yog-Sothoth is the gate. Yog-Sothoth is the key and guardian of the gate. Past, present, future, all are one in Yog-Sothoth.5

Described as a foaming mass of eyes and glowing orbs, Yog-Sothoth is said to know all and see all. It simultaneously perceives and stores all information in the universe, acting both as library and librarian. It exists coterminous to all of time and space, but is barred from accessing either (the hows and whys of this vary by author). Yog-Sothoth is also called the “Lurker at the Threshold” and exists at all points of transition, particularly those between different states of consciousness and layers of reality.

Working with Yog-Sothoth can be unpredictable. It doesn’t always respond to invocations, and typically isn’t interested in offerings or favours; it already knows what you’re doing and will make contact only if it’s interested. It can sometimes be persuaded to share some of its knowledge, or give guidance on topics such as scrying, divination, summoning, and astral travel, (and it’s always been very good advice) but only on its own terms.

Nyarlathotep

Into the lands of civilisation came Nyarlathotep, swarthy, slender, and sinister, always buying strange instruments of glass and metal and combining them into instruments yet stranger. He spoke much of the sciences – of electricity and psychology –and gave exhibitions of power which sent his spectators away speechless, yet which swelled his fame to exceeding magnitude. Men advised one another to see Nyarlathotep, and shuddered. And where Nyarlathotep went, rest vanished; for the small hours were rent with the screams of a nightmare.6

The shapeshifting messenger of Azathoth, Nyarlathotep, is often considered the most “human” member of the Cthulhu Mythos. At least, they’re the only one who takes an interest in human affairs.7 They’re also the most active, and the easiest to make contact with; other entities are said to be either exiled from physical space or in a state of hibernation, but Nyarlathotep walks the earth. Interestingly, they’re also the entity tied most closely with marginalized groups, and the one most commonly characterized as malevolent.

Nyarlathotep is a trickster and a magician. They frequently pose as other gods and entities, sometimes as a test, sometimes so their message will be listened to. They’re interested in the development of human society, in shifting paradigms and social upheavals, and often work to shock the apathetic and reactionary out of their ruts. Evidence of their passing often shows up in unexpected places. They enjoy both magick and bargains, and can become a reliable source of magical help in exchange for offerings or small favours.

Shub-Niggurath

One squat, black temple of Tsathoggua was encountered, but it had been turned into a shrine of Shub-Niggurath, the All-Mother and wife of the Not-to-Be-Named-One. This deity was a kind of sophisticated Astarte, and her worship struck the pious Catholic as supremely obnoxious.8

The resident fertility deity in the pantheon, Shub-Niggurath is said to be the most widely worshipped entity in the Cthulhu Mythos. Despite this, she appears the least in fiction — she’s occasionally mentioned in incantations or in asides by various characters, but rarely makes an appearance or has much impact on the plot. Known as the “Black Goat of the Woods,” she is said to be a cloudy mass of goat legs, tendrils, and mouths covered in shaggy black fur, who is perpetually giving birth, with some of her children being reabsorbed into her body. In my practice she functions as a hearth goddess, keeping my home harmonious so my creative work can thrive. She is also fiercely protective and can be called on for protection magick.

Cthulhu

Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn.

(In his house at R’lyeh, dead C’thulhu waits dreaming.)9

Cthulhu has become the most iconic of the Mythos, and even given his name to it. This is partly because his form is much easier to depict, and partly because he operates on a smaller, more human scale. While the other entities I’ve covered so far have been “Outer Gods,” Cthulhu is a “Great Old One,” a less powerful being more grounded in physical reality. He is the priest of the Outer Gods on Earth. He is said to sleep in R’lyeh, an ancient sunken city somewhere in the South Pacific, and from there broadcasts his dreams to those sensitive enough to receive them. If you attune yourself to this energy, you can glean advice for working with the Outer Gods, have vivid and meaningful dreams, and gain inspiration for your creative works.

Working with these beings is unpredictable, and each individual could have a very different experience, but I think I’ve given you enough to get started. Despite its less-than-progressive origins, the Cthulhu Mythos holds a lot of magical potential. What came from a place of fear can be a tool for transformation and self-love.

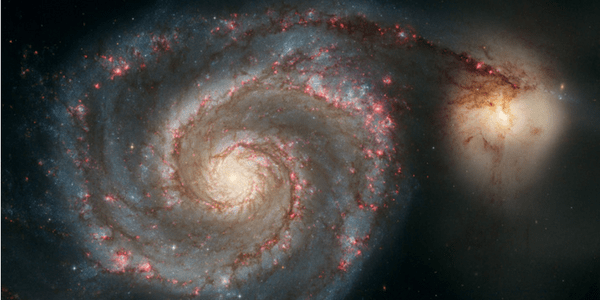

Image credits: P K, Chris Moody, Hubble Heritage, and Todd Anderson

- “The Call of Cthulhu,” The Shadow Out of Time, At the Mountains of Madness. [↩]

- Melville House, “What H.P. Lovecraft was afraid of,” 20 January 2011. [↩]

- Andi Grace, “Coming out of the woo closet: Facing shame, stigma and historical trauma,” Little Red Tarot, 20 October 2016. [↩]

- H.P. Lovecraft, “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath.” [↩]

- H.P. Lovecraft, “The Dunwich Horror.” [↩]

- H.P. Lovecraft, “Nyarlathotep.” [↩]

- Most writers use masculine pronouns but that never seemed quite right to me. [↩]

- H.P. Lovecraft and Zealia Bishop, “The Mound.” [↩]

- H.P. Lovecraft, “The Call of Cthulhu,” in The Call of Cthulhu and Other Tales. [↩]