Folklore, Horror Stories, and the Slender Man: The Development of an Internet Mythology, by Shira Chess and Eric Newsom

Folklore, Horror Stories, and the Slender Man: The Development of an Internet Mythology, by Shira Chess and Eric Newsom

Palgrave Pivot, 9781137498526, 143 pp. (incl. bibliography and index), 2015

If you weren’t already familiar with the Slender Man mythos, you likely heard about the character in connection with a grisly attempted murder perpetrated by two 12-year-old girls. In Folklore, Horror Stories, and the Slender Man: The Development of an Internet Mythology, Shira Chess and Eric Newsom describe the Slender Man as a “communally created character” that “illuminates cultural anxieties” about the patriarchy, the transition to adulthood, and surveillance culture, among other things.1 Yet, when brought into the real world, it becomes something else.

I have an interest in the Cthulhu Mythos that emerged out of H.P. Lovecraft‘s work, most notably The Call of Cthulhu, which was first published in 1926. Lovecraft was sexist, racist, and not a terribly nice guy, but he created dark gods that resonated with power, as well as loathsome creatures that chilled the spine. The mythos he spawned has since been expanded upon by other writers, and oozed into other genres, from retellings of in graphic novels and video games to lots of merch. And, of course, there are quite a lot of practising occultists (and not just chaos magicians, but yeah, also lots of chaos magicians) who work with figures from the mythos. In this respect, I have some familiarity with fictional characters who become a kind of real.

That said, despite Ian Cat Vincent‘s writings about it, the Slender Man phenomenon more or less passed me by. So, I was excited to learn what it was all about, and Chess and Newsom’s book offers a comprehensive look at how the Slender Man emerged, travelled, and offers clues as to where he might be headed next.

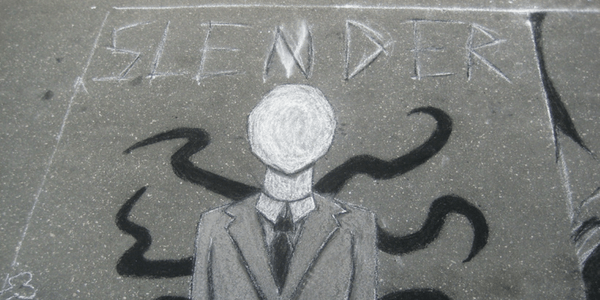

The Slender Man first appeared on Something Awful in 2009.2 Victor Surge (Eric Knudsen), responding to a challenge to create a “paranormal image” using Photoshop, uploaded first one image, and the a second, along with a brief note that included the name by which the character has become familiar, that he was faceless and stalked children. Others on the forum were taken with the idea, and the Slender Man’s mythos began to grow almost immediately.3 Interest in the character and stories about him soon spread to other websites, collectively created web series, novels, video games, and apps — fan fiction in action. As Chess and Newsom note, the “fluidity of the story gives it power.”4 The very spareness of the initial post left the Slender Man ripe for development: there was backstory to fill, symptoms to invent, other cases to be reported, and so on. That it began as fiction on a forum meant that anyone could chime in and advance the mythos. As a result, Chess and Newsom locate the Slender Man in the context of transmedia and alternate reality games, where participants co-create and recontextualize the story as it develops.5

Surge says that the original Slender Man photos and backstory took 10-15 minutes of thought. The character was inspired by another character in a film he hadn’t even seen, “Tall Man” from Phantasm. His thinking was, “What do I find scary? What do I find creepy, personally?”6 From this, the mythos grew quickly and some of the other folkloric accounts that emerged were even creepier than the original. Throughout this, Surge watched on with bemused interest.7 Yet, as it continued to expand, he became concerned about possible commercialization of the character, and copyrighted it.8 As a result, some of the more popular vectors by which the story spread used alternate versions of the name in their portrayals of faceless, tall white men who stalked children.

The contemporary horror contexts into which the Slender Man fits draws on the fear of the Other, the in group versus the out group, and the fear of the unknown. The juxtaposition of a man in a suit — urban, cultured — with his hunting grounds being forested areas — the wild — gives rise to a sense of the uncanny, as it’s inconsistent with what we might expect. Of course, his kidnapping of children is reminiscent of my folklore, as is the absence of technology (in later developments, the Slender Man disrupts attempts to record him), and in some portrayals, he can even blend into or turn into trees.

Chess and Newsom also note that the Slender Man emerged at roughly the same time as the hacktivist collective Anonymous and the anti-capitalist Occupy Movement. The Slender Man’s suit suggests a similar paternalistic conservatism. These anxieties were and remain a part of the cultural zeitgeist, which further suggests why it captured imaginations so, and so quickly.

The story was developed through webseries such as Marble Hornets, TribeTwelve, and EverymanHYBRID, which spread through YouTube, Tumblr, Twitter, Instagram, and beyond. These webseries used “found” footage and Blair Witch Project-style dramatics, and it seems like it would have been nifty to have experienced the unfolding of these narratives as the episodes appeared. That each successive iteration feeds on the myths developed in the previous ones adds to the charm of the emerging mythologies. Easter egg hunting, looking for clues, and trying to untangle the story sounds like Lost for a new generation, co-created by fans and amateurs, rather than with a big studio budget. As it was created online by people who mostly work with what they have, there’s an immediacy to it that a networked show can never achieve. The webseries could respond to audience digging and participation in the next episode — something that could not be done even by a Netflix-based show. 9

The Slender Man has even spawned parodies, and somehow acquired a family. For instance, the Splendour Man, one of the Slender Man’s “Slender Siblings,” initially arose from a newscaster’s mispronunciation of the original.10 There’s also the Trender Man, a more stylish version of the Slender Man with an interest in fashion.11 And, of course, there’s erotica. Rule 34 and all.

Chess and Newsom highlight that we can see the Slender Man’s origins and evolution in a readily traceable way. It’s rare to see the development of folklore in real time, but the Internet affords us that opportunity. This was made possible through what they all the “digital campfire,” around which users tell stories, reinventing the mythos in response to audience response and input.

Following Richard Bauman, folklore is defined as being variable, preformative and interactive, and communally co-created.12 With “digital folklore,” as they write, “[a]round the digital campfire, everyone has the capacity to contribute.”13 With digital folklore, there’s often a deliberate breaking of the fourth wall, or, in some cases, no fourth wall at all.14 However, while participation is welcomed, there are rules. Using the analogy of theatre, Chess and Newsom write, “though speaking back to the stage was often encouraged, loudly pointing out the presence of the stage was not.”15 The audience is enjoined not to “gamejack,” and to instead take the story seriously as it is told.

However, even though the Slender Man mythos ticks all the boxes for Bauman’s definition of folklore noted above, some label it “fakelore,” in part because it was digitally-born, and because it does not attempt to pass itself off as “true” in any objective sense. It’s origins on the Internet are well-documented, and even encouraged. As a result, Chess and Newsom argue that as it’s not a marketing scheme, and is legitimately community-driven, it does indeed meet the criteria required to class it as folklore.16 That said, its fictive origins still lead to real-world consequences.

In 2014, two 12-year-old girls attempted to murder another 12-year-old girl in Waukesha, Wisconsin. It was premeditated and planned in detail. Inspired by the Internet meme that became mythos: the Slender Man.17 After this revelation, links to more violent crimes emerged.18 As a result, the Slender Man has come to be associated with children in popular media, but as we’ve seen, adults also develop the lore. Chess and Newsom comment on the story that seems to haven given rise to the two girls’ interpretations of the Slender Man, and its contested nature as fan fiction in contrast to more “authorized” accounts, with the gendered implications implied. Battles over what counts as canon versus non-canon are fiercely fought in the way that only the Internet facilitates. Its most ardent fans insist that a real-life stabbing would be an “illegitimate” adaptation, and they strongly denounce the actions of these girls and others.

There’s an undeniable naturalness to myth-sharing in our culture, and sometimes these may generate new creatures — some of which may take on a non-corporeal existence. In the case of the Slender Man, this emerges as a tulpa, as filtered through the understanding of Alexandra David-Neel.19 The idea of the Slender Man as a tulpa was first suggested in the Something Awful forums, and Chess and Newsom note that the theory is compelling, because it “implies an inherently complicit audience, while providing reason for that audience’s inability to control its subject.”20

Folklore, Horror Stories, and the Slender Man: The Development of an Internet Mythology offers a comprehensive look at the Slender Man phenomenon from its origins to later developments, considers its folkloric pattern, roots in horror, and its cultural implications. Shira Chess and Eric Newsom have written a fascinating account, and those who want to learn more about the character would find this a useful read.

Image credit: mdl70

- p. 11 [↩]

- Something Awful, somethingawful.com. [↩]

- p. 16 [↩]

- p. 16 [↩]

- p. 17-18 [↩]

- p. 25 [↩]

- p. 28-29 [↩]

- p. 29 [↩]

- p. 30-35 [↩]

- p. 3 Or, “Splendor Man,” for those of you residing in the United States. [↩]

- p. 107-109 [↩]

- p. 79 [↩]

- p. 85 [↩]

- p. 87 [↩]

- p. 88 [↩]

- p. 92 [↩]

- p. 2 [↩]

- p. 3 [↩]

- p. 119 [↩]

- p. 120 [↩]