The Ecstasy of Being: Mythology and Dance, by Joseph Campbell

New World Library, 9781608683666, 264 pp. (incl. notes, index, and bibliography), 2017

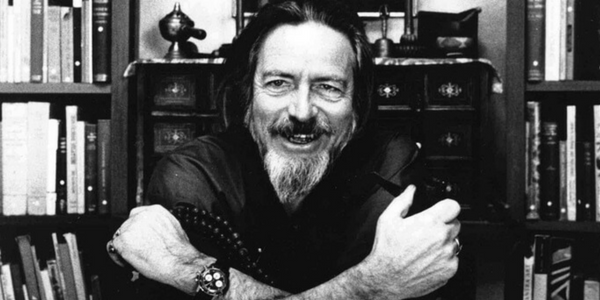

Joseph Campbell (1904-1987), the author of The Ecstasy of Being: Mythology and Dance, has become well known in occult circles for his writing on comparative mythology and the common themes that myths seem to share across cultures. His work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and his collaboration with Bill Moyers to create the PBS series The Power of Myth, introduced many to the concept of the hero’s journey. The hero’s journey, with its structure of the call to adventure, the trials the hero faces, and the hero’s eventual return to the world having undergone a transformation, has been applied as a structure for everything from art, to fantasy stories, to initiatory rituals.1

Joseph Campbell (1904-1987), the author of The Ecstasy of Being: Mythology and Dance, has become well known in occult circles for his writing on comparative mythology and the common themes that myths seem to share across cultures. His work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and his collaboration with Bill Moyers to create the PBS series The Power of Myth, introduced many to the concept of the hero’s journey. The hero’s journey, with its structure of the call to adventure, the trials the hero faces, and the hero’s eventual return to the world having undergone a transformation, has been applied as a structure for everything from art, to fantasy stories, to initiatory rituals.1

The Ecstasy of Being is the latest book published as part of The Collected Works of Joseph Campbell series, as maintained by the Joseph Campbell Foundation, and it is broken into two sections. “Part I: Articles and Lectures” consists of eight articles and lecture transcripts on the subject of dance that span the years 1944-1978. “Part II: Mythology and Form in the Performing and Visual Arts,” is comprised of the first publication of a manuscript that Campbell was in the process of completing before his death in 1987. It also includes a forward by the book’s editor Nancy Allison, an extensive notes section, index, and a bibliography of Campbell’s works.

I cannot write this review without including a note on the language in the book. It is important to remember that, despite its 2017 publication date, what’s included in its pages was written decades ago; all but one of the collected articles and lectures included in Part I are from 1950 or earlier. The text makes use of male pronouns as if they are inclusive of everyone, and there are certain words used to designate people of colour that, while not considered appropriate today, would have been used commonly in academic circles at the time. In addition, most anthropologists today would not use the word “primitive” to refer to a living culture, as Campbell does when referring to some cultures mentioned in the first part of the book.

Campbell’s writing style tends towards what some might call academic, and you can certainly hear the professor in his literary voice. However, there is also a passion for his subject that’s very present in his writing. At times, such as when he refers to how, in modern western culture, “the whole spirit of the ancient symbols is now lost to us. We no longer sense the supporting presence of the animal ancestors; we no longer live the cosmic drama of the heavens,” his tone becomes one of lament that many practitioners of modern earth-focused spirituality can likely identify with.2 The first half of the book focuses greatly on this loss and, particularly its loss in connection to dance, which in in the west has moved from the communal sharing of story and myth, to the stage where it has become “a sort of fashionable after-dinner entertainment for people able to afford expensive evenings.”3 He contrasts our modern take on dance to traditional and communal dances of the Andaman Islands and the hula of Hawaii, as well as others, and finds our western presentation to lack the connection to spirit noted in the quote above. Campbell expresses a definite sense of longing for there to be something more.

Part II explores how western artists from a variety of traditions have sought to bring this spirit back into their art forms through their exploration of myth and the living traditions of other cultures. He references visual artists, poets, and dancers who explored ancient mythological themes in their work. Referencing works by Pablo Picasso, W.B. Yeats, Michio Ito, and Isadora Duncan, he highlights how early 20th-century artists began to use mythological themes and cultural traditions from the east to move beyond the boundaries of what was considered art. He further explores the mythologically-inspired works of other dancers, including Martha Graham and Jean Erdman (his wife), as well as the composers such as John Cage, who created the scores they moved to.

Mythology and Form in the Performing and Visual Arts was not a final manuscript and was still in progress upon his death, and it does have a bit of a feeling of being unfinished. As a dancer and a practicing witch who makes use of movement and song in my celebrations and public rites, I identified deeply with the sense of loss Campbell so often expresses in this work, and the sense of hope he shares when examining the works of modern western artists who seem to be on a similar quest for this connection. I also found myself asking what Campbell might have thought of the modern Pagan movement as it exists today, and how many of us are actively working to reconnect to the “supporting presence of our animal ancestors,” and trying to find our place in “the cosmic drama of the heavens.” It is a path that, while not always clear to us, is perhaps a little easier for us to find and travel upon, thanks to the work of those, such as Campbell, who have come before us.

The Ecstasy of Being is certainly a recommended read for anyone who is a fan of Joseph Campbell’s work, but also for anyone who wishes to understand the connection and interplay of art and spirit, how the two were parted, and how we might begin to explore reuniting them, not only on the stage but within ourselves.

- “About Joseph Campbell,” The Joseph Campbell Foundation, n.d. [↩]

- p. 49 [↩]

- p. 61 [↩]