The Kabbalistic Mirror of Genesis: A Commentary on the First Three Chapters, by David Chaim Smith

The Kabbalistic Mirror of Genesis: A Commentary on the First Three Chapters, by David Chaim Smith

Inner Traditions, 978-1620554630, pp. 224, 2015

Given the widespread availability of numerous books on esoteric topics these days, it is rare to find a book that breaks new ground. The Kabbalistic Mirror of Genesis: Commentary on the First Three Chapters of Genesis, by David Chaim Smith, is just such a book. It offers a unique perspective on one of the bible’s most well known myths, and presents kabbalah in a nondualistic and nontheistic fashion.

Smith tackles the familiar biblical myths of creation, the Garden of Eden, and the fall, but interprets them in a way that has nothing in common with the dogmatic interpretations of fundamentalists. Compared to Smith, even supposedly esoteric interpretations actually appear quite ordinary, as his account deconstructs the conventional cognitive categories of causality, time, and space.

The Kabbalistic Mirror of Genesis is not a text for beginners new to kabbalah. It is dense, uses complex language, and assumes some familiarity with kabbalistic terminology, including the sefirot and divine names. (Readers who are looking for a more general introduction to traditional kabbalah may want to seek out Aryeh Kaplan’s book Inner Space: Introduction to Kabbalah, Meditation and Prophecy.) However, for esotericists with an interest in kabbalah and gnostic contemplation, the book is a hidden gem. It presents a truly radical perspective, a perspective that is aligned with other nondual mystical traditions, as well as with magical currents such as Hermeticism and Thelema.

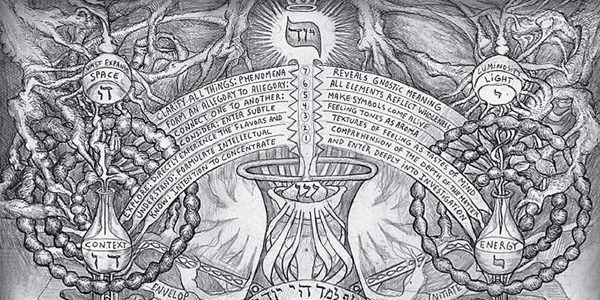

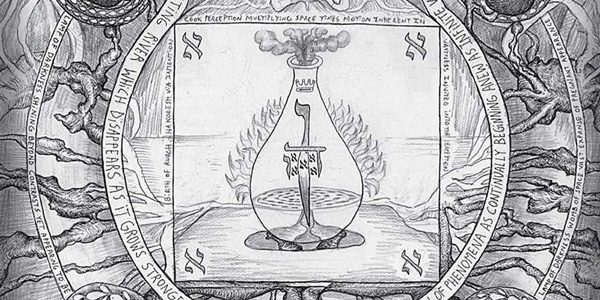

A version of the text was originally published by Daat Press in 2010, but it has recently been republished by Inner Traditions. The new version is most welcome, as the original was expensive and difficult to obtain, and the work deserves to find a wider audience. The new edition has gotten a makeover; improved formatting and layout make the complex text easier to follow, and the publishers have included several of Smith’s intricate black and white esoteric illustrations. These beautiful illustrations serve as kabbalistic mandalas, and offer a gateway for gnostic contemplators who seek to engage the text on a deeper level.

The text itself analyzes Genesis 1 – 3 in a rigorous and systematic fashion. According to Smith, Genesis 1 can be read as a blueprint of “the dynamic nature of creativity that presents total possibility.”1 He correlates passages from the creation myth with divine names and kabbalistic sefirot, and specifically links the six days of creation with the six sefirot from Chesed to Yesod. While his interpretation is rooted in traditional kabbalistic texts, Smith presents a radically nondualist point of view by rejecting “all conventional assumptions about the solidity of substance, the linear cohesiveness of time, and the integrity of thought.”2

The creation of the universe is therefore not a singular event that occurred in the distant past. Rather, it is an ongoing process that occurs outside the conventional framework of time and space. For this reason, Smith rejects the idea that the sefirot emanated from Ain Sof in a linear fashion. According to Smith, “the ten sefirot are not a representation of a linear, stepped-down hierarchy, which beings at keter and concludes at malkut… They present Ain Sof as a unified interdependent whole.”3

Smith’s exegesis continue with a discussion of Genesis chapter 2 and the Garden of Eden. Smith writes that “the central message of the Edenic allegory is that when perception does not obscure Divinity, everything is bliss… When they are not obscured through self-serving concerns and illusions, all phenomena are the Garden of Eden.”4 Smith’s account of Eden echoes ideas found in other nondualist mystic traditions, such as the Vajrayana school of Buddhism. It is a gnostic vision that one also finds in William Blake‘s poetry; for instance, in “Auguries of Innocence,” where Blake writes: “To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower.”

In Genesis 3, we encounter the famous myth of Eve, the serpent, and the fall. Smith maintains his radical analysis of the Genesis myth by rejecting all conventional religious interpretations of the fall from Eden. For Smith, the fall has nothing to do with moralistic notions of temptation and sin. Rather, the fall describes the state of ordinary human consciousness when it habitually engages with reality from the standpoint of conventional fixations, and manufactures “endless egoic nightmare scenarios.”5

For Smith, the symbol of the serpent is a key that can help liberate us from problematic cognitive habits. In language reminiscent of the ancient gnostics, Smith writes, “the serpent is the great unsung hero of all biblical literature… The gnostic understanding of the serpent represents the untainted possibility of a morality that adjusts to the needs of the mind before any authoritarian code, freed from the shackles of dogma and pedantic convention. If it is not rejected as pure evil, this is what it can be.”6

I have studied the original version of this book for several years now, and it has had a profound impact on my own contemplative practice. Every page offers new insights, and the mere act of reading this text often seems to bring about subtle shifts in consciousness. I sincerely hope that the book will benefit other mystics, gnostics, and magicians, just as it has benefitted me.

I believe that The Kabbalistic Mirror of Genesis is essential reading for any esotericist who has a genuine interest in kabbalah; I have no doubt that it will someday be considered a classic. The book presents a magical vision of reality where “all notions of place and time are only contextual constructs fabricated by conventional habit, which the inner symbolism of Genesis teaches us to resist.”7

- p. 13 [↩]

- p. 13 [↩]

- p. 36-7 [↩]

- p. 125, author’s italics [↩]

- p. 189 [↩]

- p. 151-3, author’s italics [↩]

- p. 24 [↩]