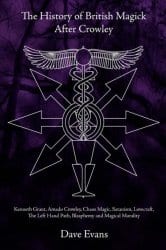

The History of British Magick After Crowley: Kenneth Grant, Amado Crowley, Chaos Magic, Satanism, Lovecraft, The Left Hand Path, Blasphemy and Magical Morality, by Dave Evans

The History of British Magick After Crowley: Kenneth Grant, Amado Crowley, Chaos Magic, Satanism, Lovecraft, The Left Hand Path, Blasphemy and Magical Morality, by Dave Evans

Hidden Publishing, 97895523700, 435 pp. (incl. appendix, bibliography and index), 435 pp. (incl. appendix, bibliography and index)

I’ve known Dave Evans online for a number of years, so I was excited when he said his book had finally been published, and looked forward to reading it. His doctoral dissertation in history forms the basis for The History of British Magick After Crowley, and as such it is structured in an academic format, opening with a detailed explanation of his methodology, and his involvement with both magick and academia.

Magicians are not known for their strict adherence to objective truths, and much of the traditions are oral, or rely on in-person contact. The academic approach taken with his work may seem threatening to some, challenging myths and records which have endured simply because they’re oft repeated. Evans has done an admirable job sifting through the available data to bring us what can be verified, and provided a detailed record of his sources.

This is a study in magical thought in the 60 years since Aleister Crowley‘s death. Evans writes that “…although Ronald Hutton makes the excellent point that in the last 50 or so years Britain gave Wicca to the world, I would add we also gave it Chaos magick and Thelema.” Indeed, chaos magick, a more recent current which emerged about 30 years ago, and the philosophy behind seems to subtly inform much of the work — not terribly surprising as Evans comes from a chaote background.

Elusive figures are tracked down and put into perspective, such as Evans’ exploration of what’s known of the life and works of Kenneth Grant, and devotes a significant amount of time to critically examining the claims of “Amado Crowley,” the self-proclaimed son of Aleister Crowley. Though in the latter case, the space dedicated seems excessive, and indeed it sounds like there is enough to be a book’s worth on its own, and may have served better elsewhere, as Amado’s contributions to modern magick have been, to be generous, negligible.

In conclusion, Evans writes “I trust that this work has performed several tasks, not the least that it shows the utility of investigating such a subject, which although a minority activity, informs many wider beliefs and societal activities, such as interests in folklore, the urge to religious belief in general, superstition and in the realm of self-understanding, we live in a society and culture in Britain which is steeped in magical history, and to understand more about the nature of magic allows us to understand more about our own histories, our own culture, and to a large extent, our own selves.”1 In this he has succeeded well.

The stylistic inconsistencies can sometimes be confusing, but do not detract from the text. It is also repetitive at times, but for those not familiar with the characters involved, this may be helpful.

DaveEvans is that strange and rare combination of magician and historian, and with The History of British Magick After Crowley he has produced a useful source book for students of both disciplines.

- p. 319-392 [↩]