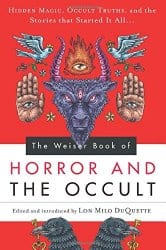

The Weiser Book of Horror and the Occult, edited and introduced by Lon Milo DuQuette

The Weiser Book of Horror and the Occult, edited and introduced by Lon Milo DuQuette

Weiser Books, 9781578635726, 352 pp., 2014

Unless you are fortunate enough to have been raised in a coven or born to a jackal, the odds are good that your first introduction into the worlds of magick and the occult probably came from the realms of fantasy and horror.

This was the case for esteemed occultist Lon Milo DuQuette, an Enochian expert, demonologist, and member of the Ordo Templi Orientis. In the introduction to The Weiser Book of Horror and the Occult, DuQuette discusses a typical rebellious childhood in the American Heartland of Nebraska in the 1950s: a world of Aurora Monster kits, paranoid sci-fi thrillers radiating from black and white cathode rays, and the subconscious darkness that has always haunted the American psyche.

DuQuette started reading horror out of protest. He had been swept away from the cutting edge of the Space Age, Southern California in the early ’50s, and transplanted to the dreary, backwards cornfields of Nebraska. The American Heartland proved to be an ideal setting for the author to discover the creeping thrills of classic horror, ploughing his way through Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination Vol. 8, armed with an Oxford dictionary and the World Book Encyclopedia.

He describes the setting, and its importance, in poetic detail, in the introduction to Horror and the Occult:

Horror takes its time, and to properly appreciate it you must also take your time. It has a pace, a slow, incessant rhythm-like your own heartbeat, or your own breath. After all, the great innovators of the art were writers of the Gilded Age who wrote for a nineteenth- and early twentieth-century audience. Nebraska in 1957 could just have easily been 1857, accompanied by the same soundtrack of bucolic silence; the same light searing through the same sun-stained yellow window shades; no hint of modern objective reality, no diversions of bustling civilization; no diversions of airplanes roaring overhead, no freeways in the distance, no sirens, no radio, no air-conditioner; only the white noise of a million cicadas and the hiss of my own blood running through my brain, the incessant swing of the pendulum of an ancient clock, the barking of a distant dog, the cawing of a crow, the almost imperceptible whisper of the delicate film of curtains as they billowed gently towards me like the gossamer negligee of a lovesick ghost.

The silence of Nebraska in the ’50s was the necessary catalyst to break the spell of the modern world, and allow space for DuQuette’s imagination to catch fire, inspiring his own creativity in turn. If this was mandatory in 1957, it’s a million times more so, in 2014.

One more quick quote from the intro:

Twenty-first century readers, spoiled by spectacular effects of the cinema, demand instant gratification from the written word-explosive shocks and gore-splattered attacks upon the senses. We no longer allow ourselves time to refine the rapture of terror. We wolf down the junk food snacks of violence and carnage when, with just a little patience, we could leisurely savour a rich and soul-satisfying banquet of elegant horror. We are missing so much.

All of this, by way of introduction, for this new collection of classic horror, from the esteemed Weiser Books, purveyors of fine esoterica for nearly 60 years. So what is a metaphysical book company doing putting out a collection of supernatural fiction?

The stories encompassed within this anthology were published from 1886 and 1923, many of which have been anthologized regularly. The authors range from leading lights; M. R. James, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Bram Stoker, Edgar Allan Poe, H. P. Lovecraft, Arthur Machen, Ambrose Bierce, Aleister Crowley, and Dion Fortune, to the more obscure, like Lovecraft’s contemporary Robert W. Chambers, and lesser-known Victorians like Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton and Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu.

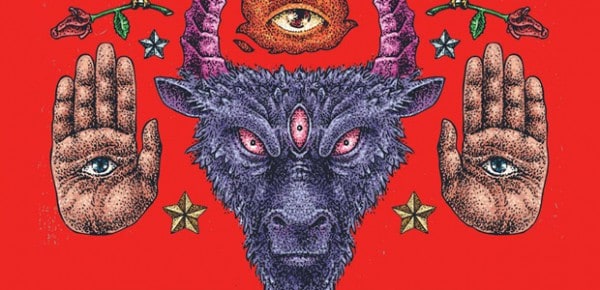

What all of these others have in common, and why they appear in this collection, is either a direct and acknowledged involvement with the occult, most specifically in the cases of Aleister Crowley and Dion Fortune, although some speculate that Bram Stoker was a member of the Golden Dawn, to stories that exemplify supernatural secrets and occult truths, such as in the case of H. P. Lovecraft, one of the greatest 20th century horror authors, who was also a lifelong skeptic and atheist.

The themes range from a whole trunk full of classic haunted house and ghost stories, “The House and the Brain” by Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, “No. 252 Rue M. Le Prince” by Ralph Adams Cram, and the excellent “Casting The Runes” by M. R. James, to tales of witchcraft (“Luella Miller” by Mary E. Wilkins Freeman), Egyptology (“The Ring of Thoth” by Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) to reincarnation (the dread and wonderful “Ligeia” by Edgar Allan Poe).

Much of the work contained in The Weiser Book of Horror and the Occult would be considered supernatural fiction or suspense by today’s standards. Consider the case of “The Messenger” by Lovecraft’s contemporary Robert W. Chambers, with its tales of a cursed monk in a sleepy provincial French hamlet. It’s ominous, to be sure, with its harbinger of doom, the death’s head moth, flopping around like a drowning fish on the hearth rug, its black, stormy nights, its mass graves. The furnishings are lovely, a sure delight for any fan of morbid literature, but you sense the end coming, practically from the beginning. There’s no twists, turns, no special hook, to snare your soul into despair. It’s just a lovely ghost story, featuring a surprisingly healthy and balanced relationship for unenlightened times.

At the very least, the atmosphere alone will make this collection a necessary addition to the supernatural library. For instance, consider the strange suite of infernal rooms from “No. 252 Rue M. Le Prince” by Ralph Adam Crams, with their black lacquered walls and domed ceilings, “like the inside of an enormous Japanese box,” and a red lacquer idol, described by the narrator as “The most astounding, misshapen, absolutely terrifying thing, I think, I have ever saw.”1 For horror junkies, this kind of setting is like opium, sending the imagination into wild paroxysms, and is worth the admission fee, alone.

There’s also the dimly lit interior of the Egyptology wing of the Louvre, in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Ring of Thoth,” with its story of immortality and doomed romance. It’s another case that is more magical realism than horror, but the trappings of distant times and far off climes is just as satisfying, for those with a flair for the fantastic.

So again, what is horror, and what does it have to do with the occult? The key lies in the famous monologue from Arthur Machen’s infamous “The White People,” delivered by a knowledgeable hermit in an opium reverie in the snugness of the hearthside:

What would your feelings by, seriously, if your cat or your dog began to talk to you, and to dispute with you in human accents? You would be overwhelmed with horror. I am sure of it. And if the roses in your garden sang a weird song, you would go mad. And suppose the stones in the road began to swell and grow before your eyes, and if the pebble that you noticed at night had shot out stony blossoms in the morning?”2

So this is horror: a feeling of things being not quite right. Things that go against the status quo, against the normal operations of waking life, common sense, and consensus reality. In this way horror, the supernatural, magick and madness are all bound together. And while the blunt force trauma of modern horror and horror cinema immediately throws up psychic shields, in pure reptile brain panic mode, horror literature subtly creeps in. It undermines your sense of concrete reality. You’re just not sure what to think any more. And what is that knocking sound?

A good example of this creeping menace is in “The Testament of Magdalen Blair,” by the “wickedest man on earth,” Aleister Crowley. “The Testament” tells the story of Magdalen Blair, a young and gifted clairvoyant who marries her professor, a man impressed by her feminine charms and psychic abilities. They were as close as a married couple could be, despite the professor being a raging atheist.

Professor Blair contracts an unknown and debilitating disease, from which he suddenly perishes, before he has a chance to absolve his sins. Most of the story takes place after the unquiet death, as Magdalen remains psychically linked to the professor, and she experiences first hand what lies in store for the unbelievers, after death.

It’s both the most authentically disturbing, being legitimately disgusting at times as the deceased is dissolved in an ocean of stomach acid for all eternity, as well as being the most theoretically sound, absolutely stuffed with asides like “We can only express a new idea by combining two or more old ideas,”3 and “The sense of consecution itself was destroyed; things sequent appeared as things superposed or concurrent spatially; a new dimension unfolded; a new destruction of all limitation exposed a new unfathomable abyss.”4

Crowley reveals himself to be both a master of modern metaphysics, and almost as gifted at writing chilling, disturbing prose. I’ve long been an admirer of the Great Beast, and have learned much of what I know from his dense texts, but I have issues with some of his attitudes as well as his followers, and things perpetuated in his name. Reading this invites a fresh appreciation of the man and his creative talents, beyond all the hype.

Reading The Weister Book of Horror and the Occult is kind of like Magdalen Blair sitting shiva with her deceased partner, as her mind is washed over with supernal information she has no way of relating to or processing.

Horror is one way to approach the absolute, and the slow subtlety, and the internal nature of literature, by nature, makes it deadly effective, in this regard. As you read this gorgeous tome, with the usual lavish production and layout Weiser is known for, the ground softens beneath your feet. The walls seem to breathe, and the wind whispers to you. This is the pathway to magick, as well as madness. It’s up to you to decide how far you want to go.

Of course, metaphysical transmissions aside, it’s nice to have so many masterful artists contained between the covers. I adored the opportunity to reread Poe, which had a similar effect on me as the editor. I have found myself falling in love again with the poetry of the English language. I appreciated the opportunity to revisit some old favourites, like Machen and Lovecraft, as well as discover some new voices, like Mary Freeman and Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, both of whom I will be reading further.

Take this opportunity to get quiet, to slow down the world, and let mysteries unfold. Some will surprise you, and some might shatter your peace of mind, but it is the pathway to wonders, guaranteed.