Everyone loves a mystery. And few things are more mysterious than occult symbols. Magicians and artists have long embraced the visual language of occultism with its tantalizing promise of hidden meaning lurking just below the surface. Judging from the capacity crowd queuing out the door for the Language of the Birds opening reception this frigid January evening, everyone here loves the mystery of occult art.

The exhibition Language of the Birds manages the seemingly impossible task of representing the breadth of occult art in the past century through a selection of 88 works currently on display at New York University’s 80WSE Gallery. A wide range of artists, styles, and mediums make up the exhibition, as explained by the show’s website:

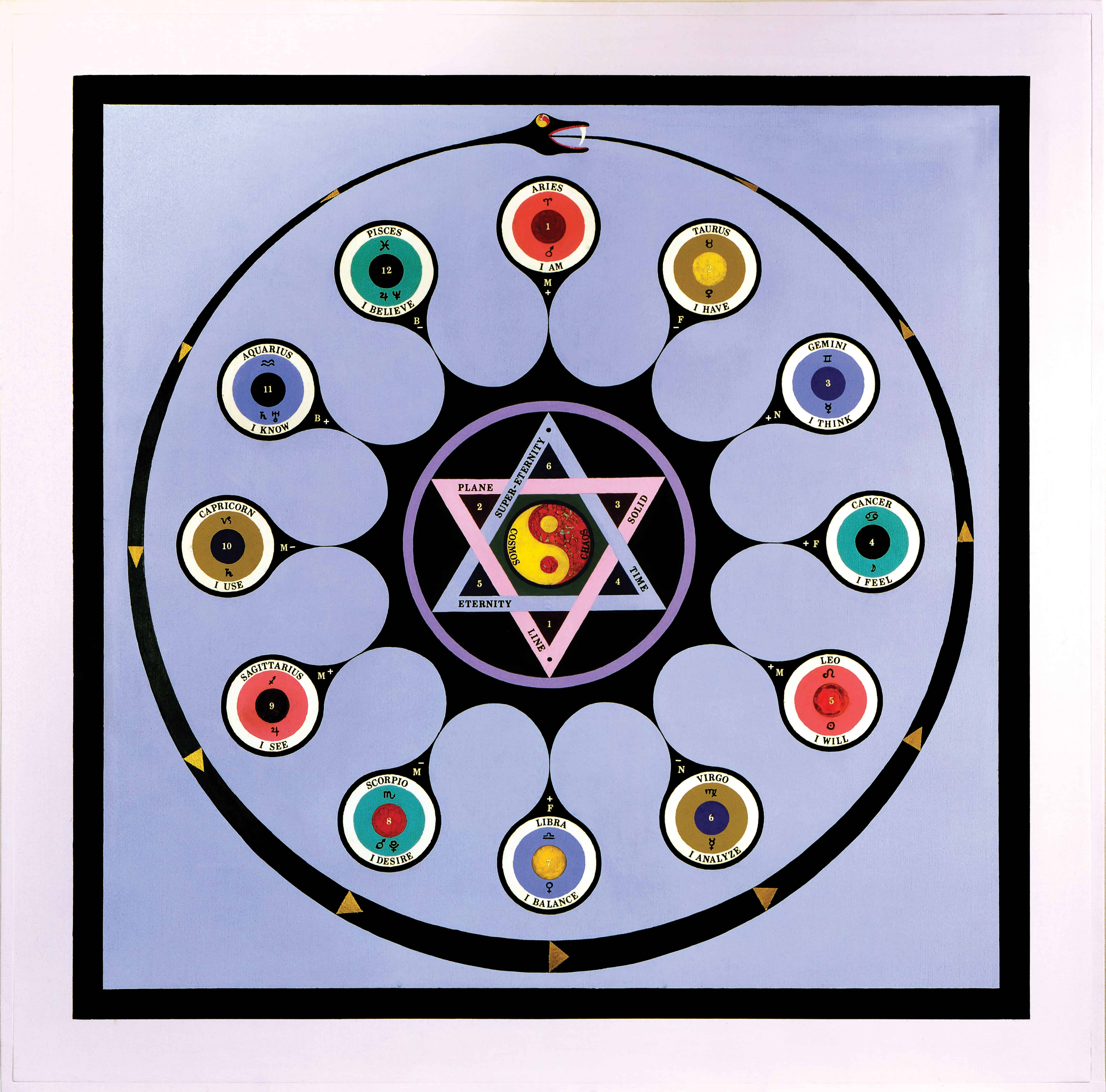

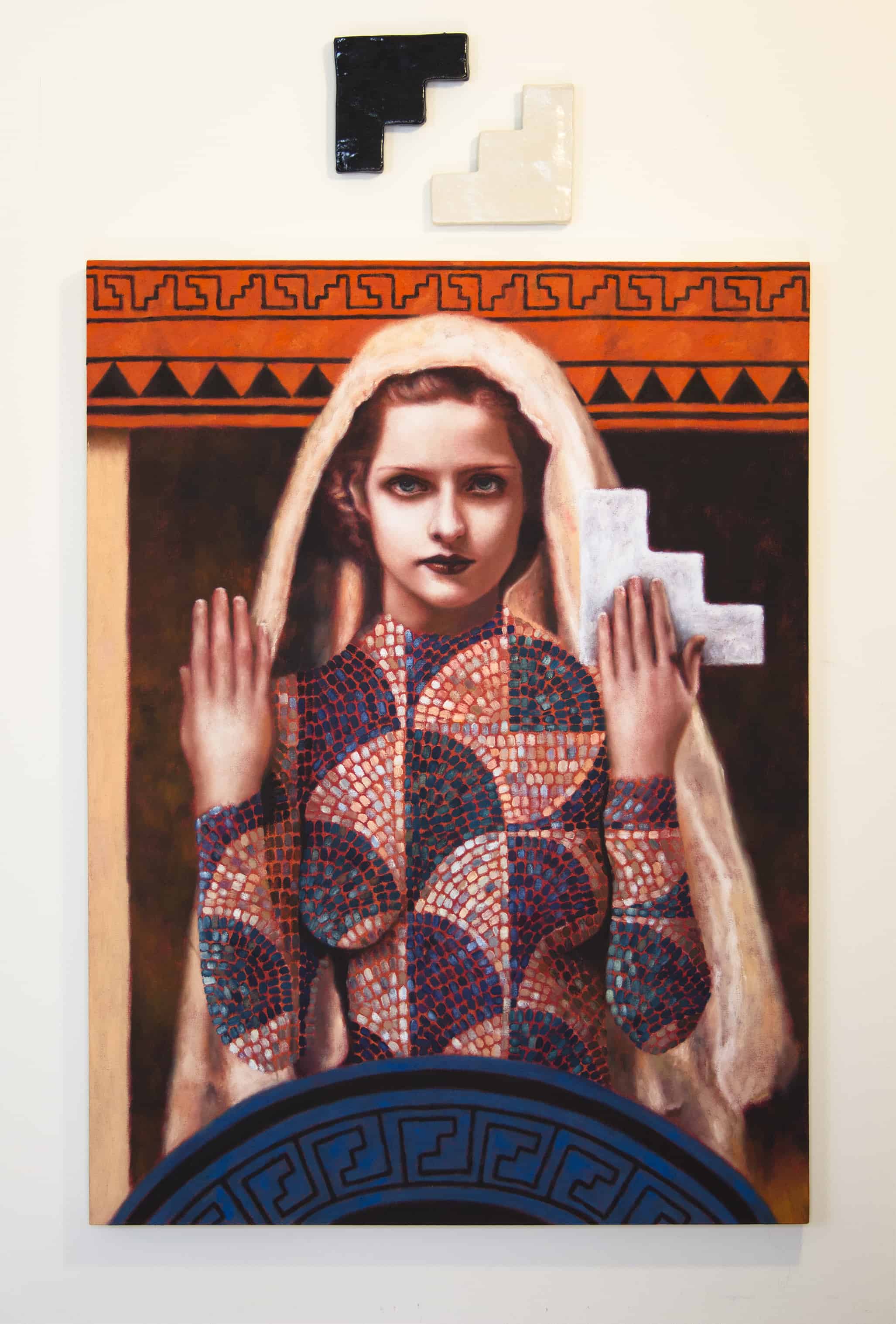

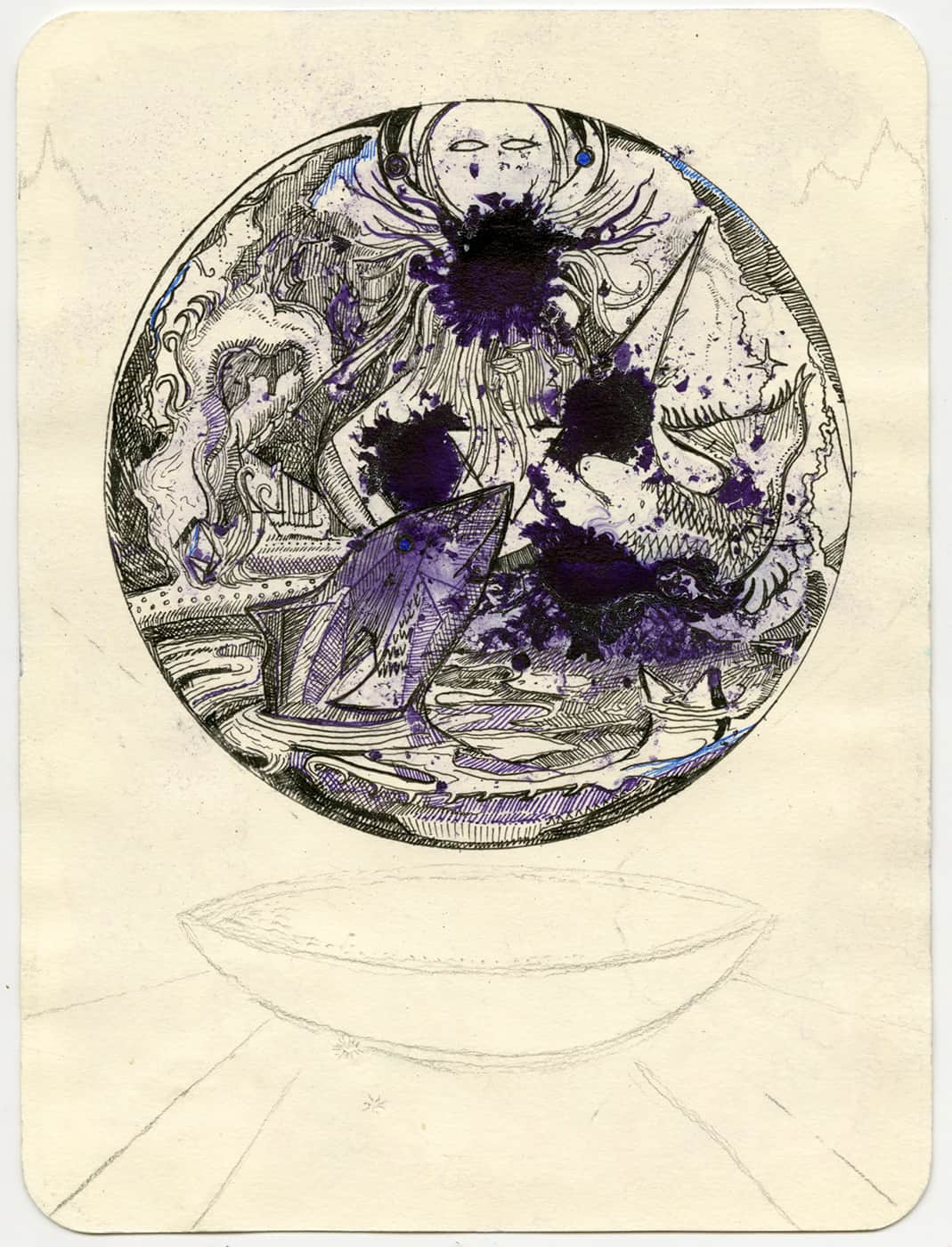

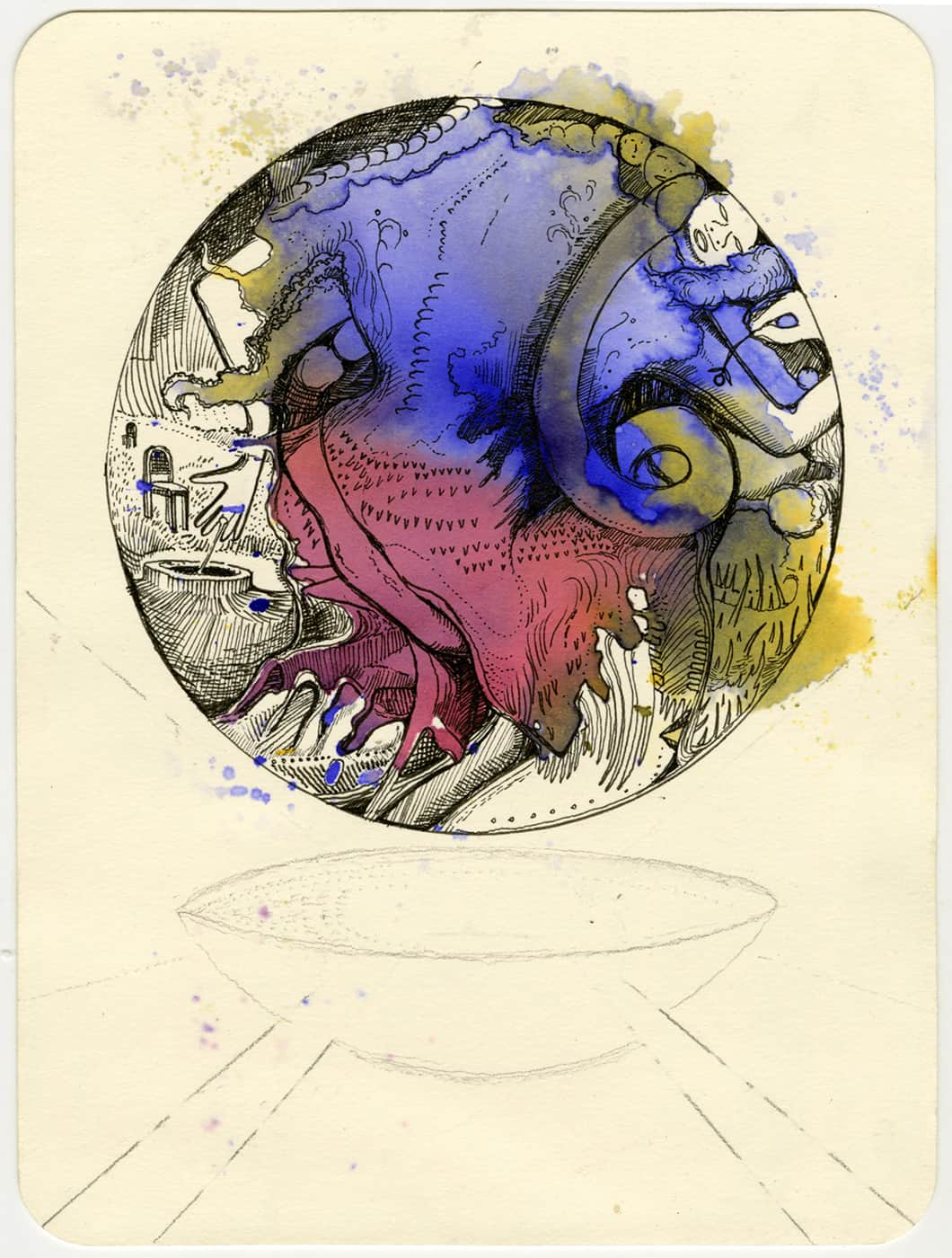

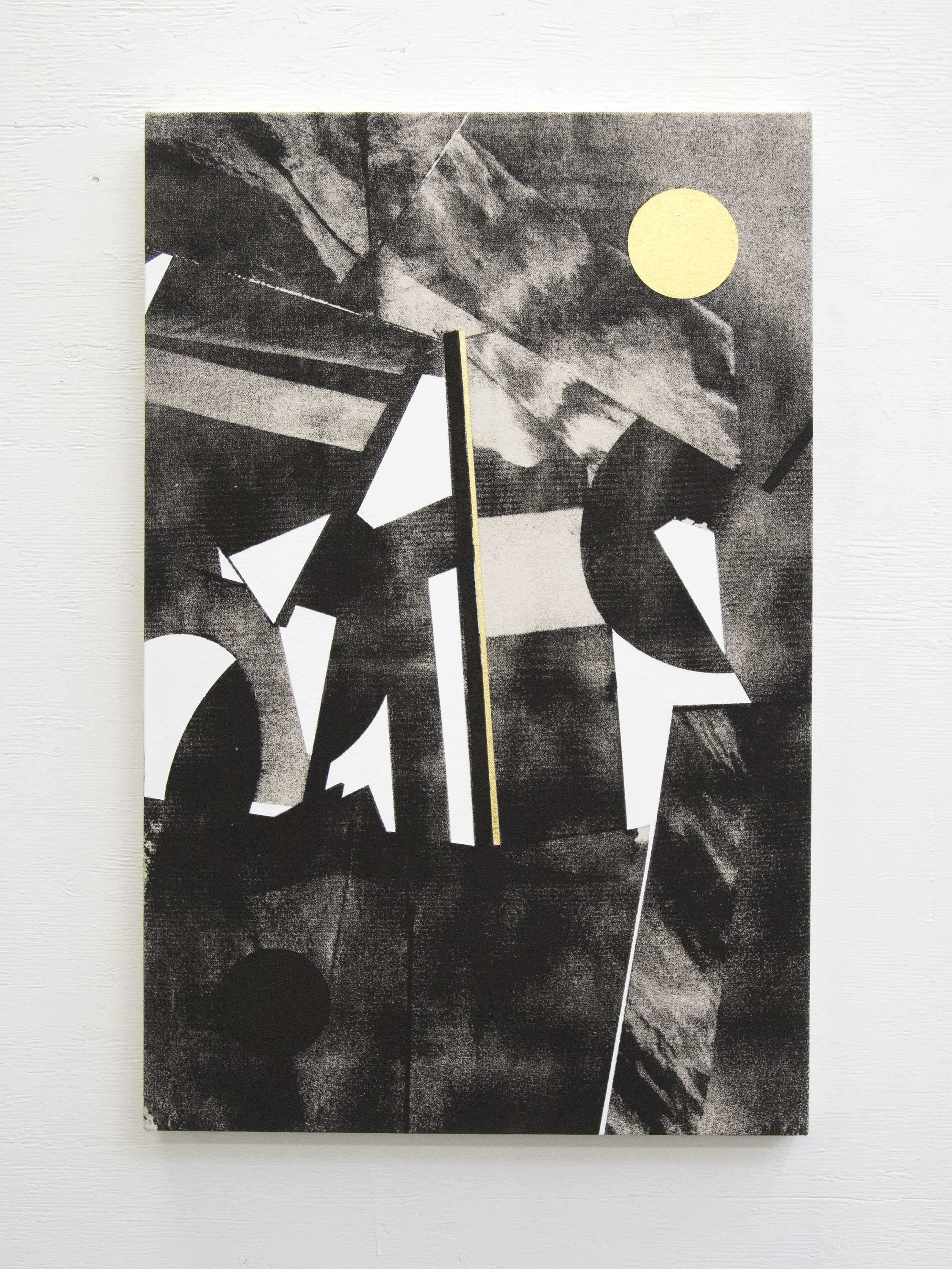

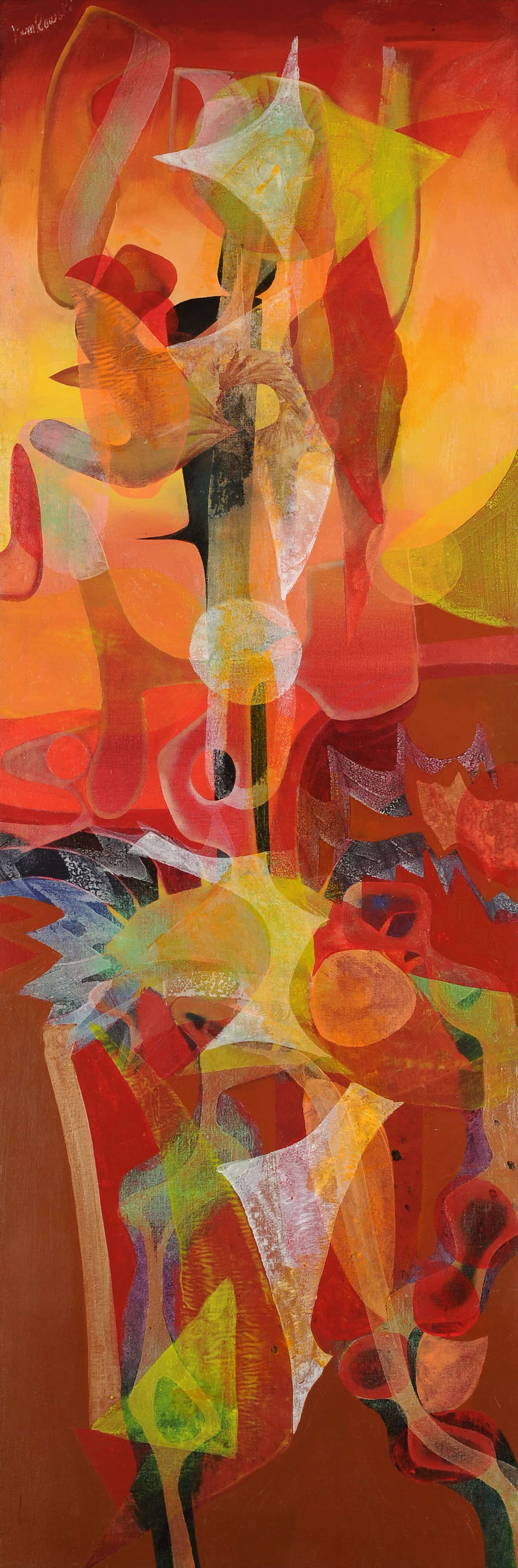

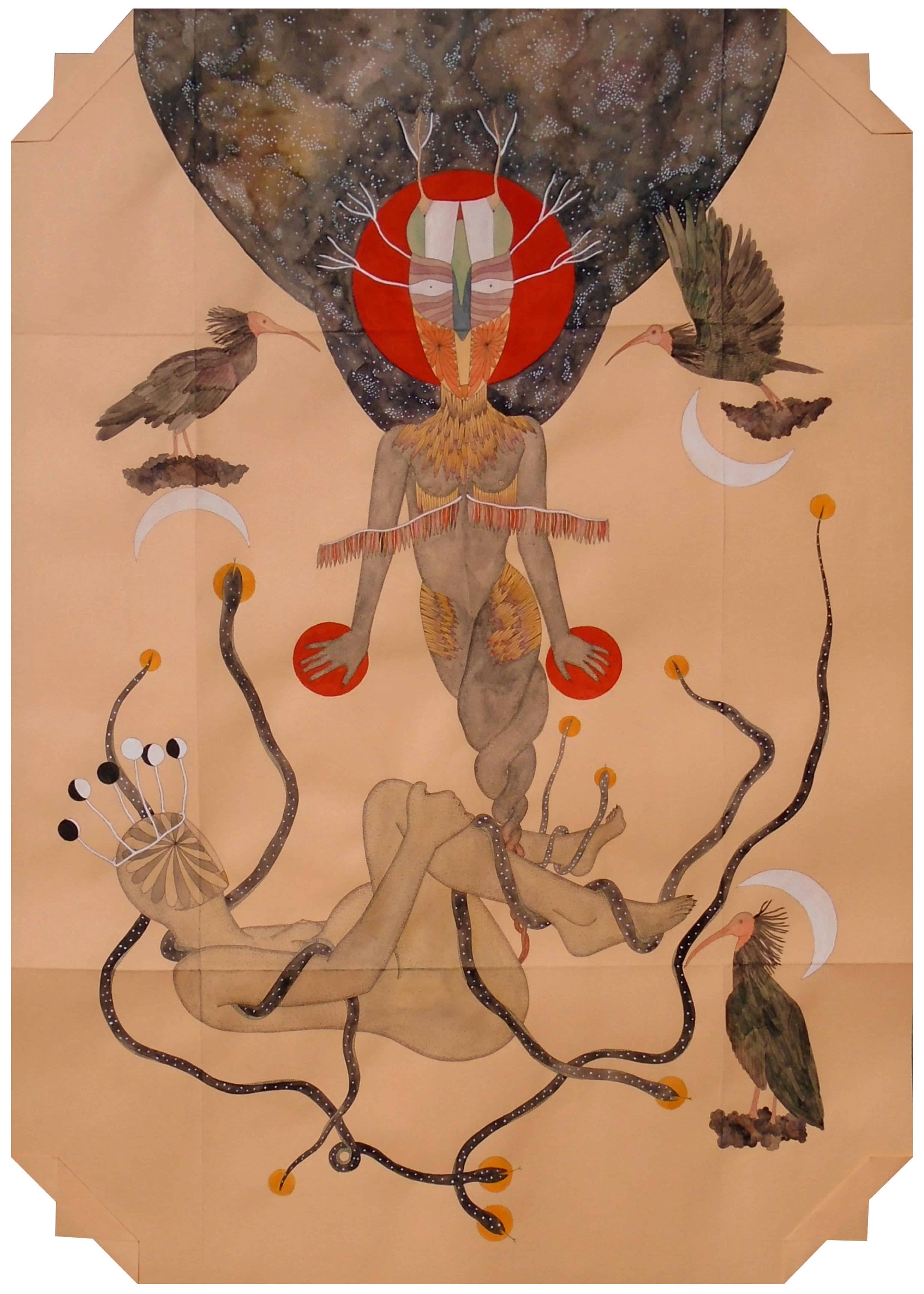

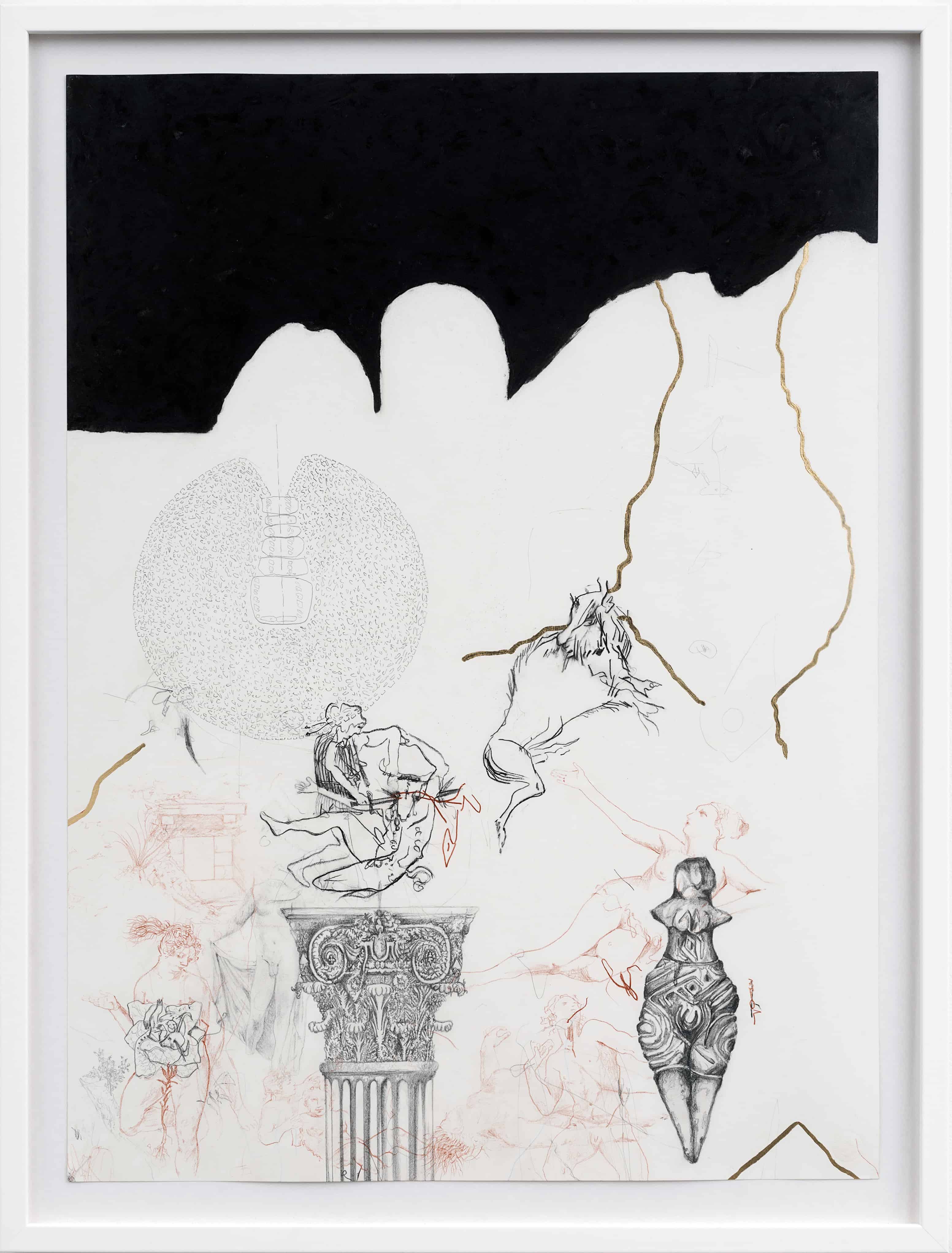

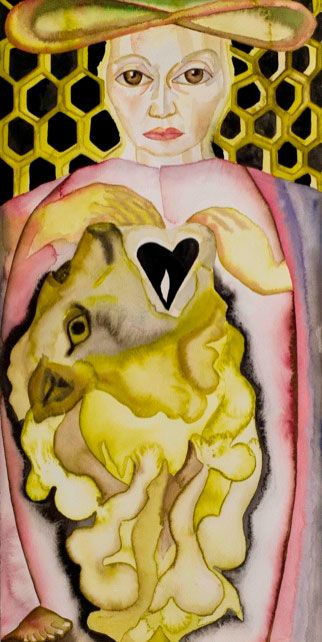

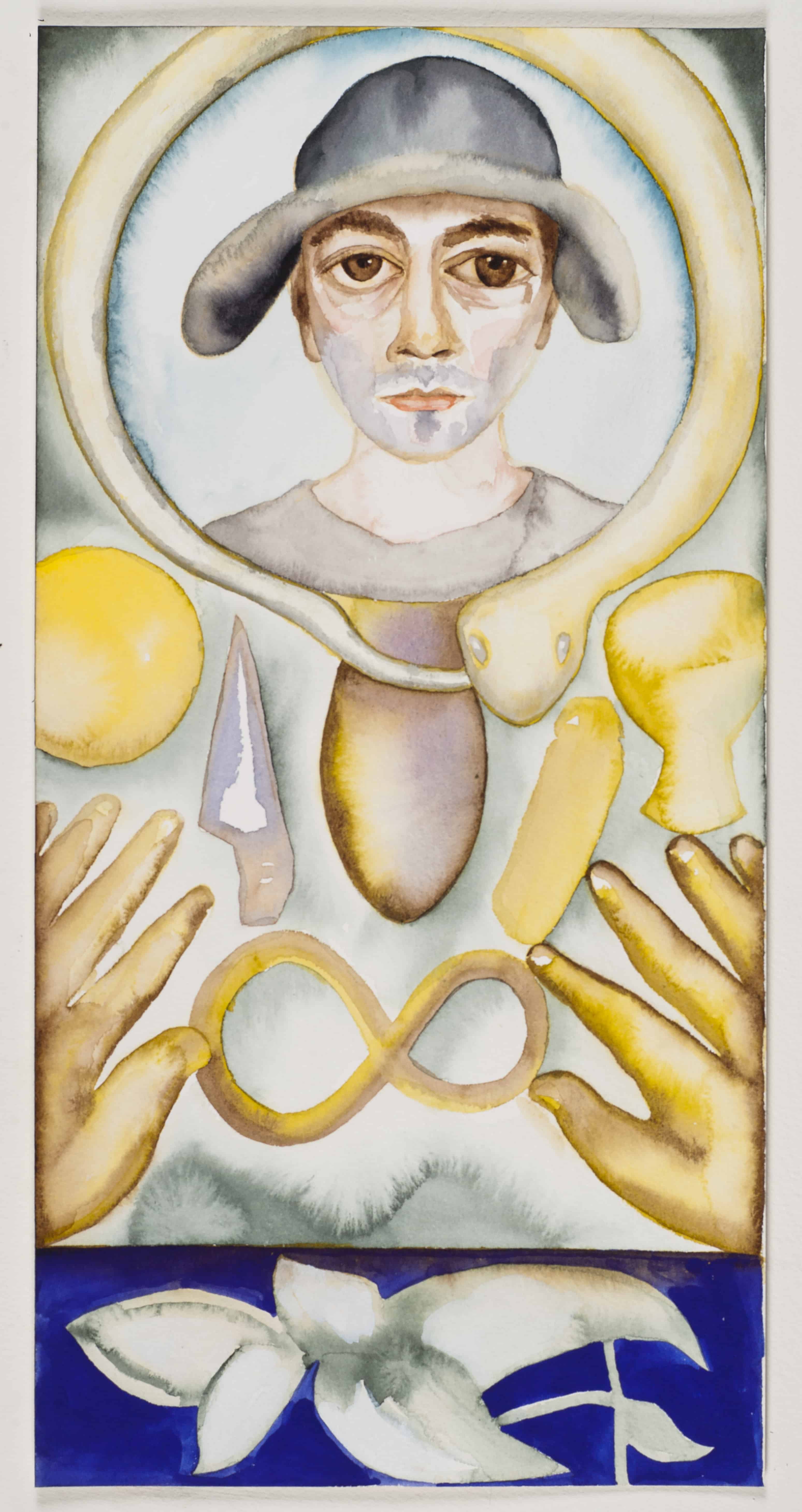

Language of the Birds: Occult and Art considers over 60 modern and contemporary artists who have each expressed their own engagement with magical practice. Beginning with Aleister Crowley‘s trance portraiture and Austin Osman Spare‘s automatic drawing of the early 20th century, the exhibition traces over 100 years of occult art, including Leonora Carrington and Kurt Seligmann’s surrealist explorations, Kenneth Anger and Ira Cohen’s ritualistic experiments in film and photography, and the mystical probings of contemporary visionaries such as Francesco Clemente, Kiki Smith, Paul Laffoley, BREYER P-ORRIDGE, and Carol Bove.

From Odin’s twin raven informers in Norse mythology, to Poe’s The Raven or the Raven King in Jonathan Strange and Mister Norrell, birds of all kinds have long been associated with hidden wisdom and used for prognostication. Those who could speak their magical langue verte were said to hold the keys to occult knowledge. And so Language of the Birds takes its name from this ancient tradition.

The show is curated by Pam Grossman, creator of the Phantasmaphile esoteric art and culture blog, associate editor of Abraxas: International Journal of Esoteric Studies, and co-organizer of NYU’s Occult Humanities Conference, which takes place in 2016 on February 5–7 in conjunction with the Language of the Birds show.

The exhibition groups its pieces into five thematic galleries:

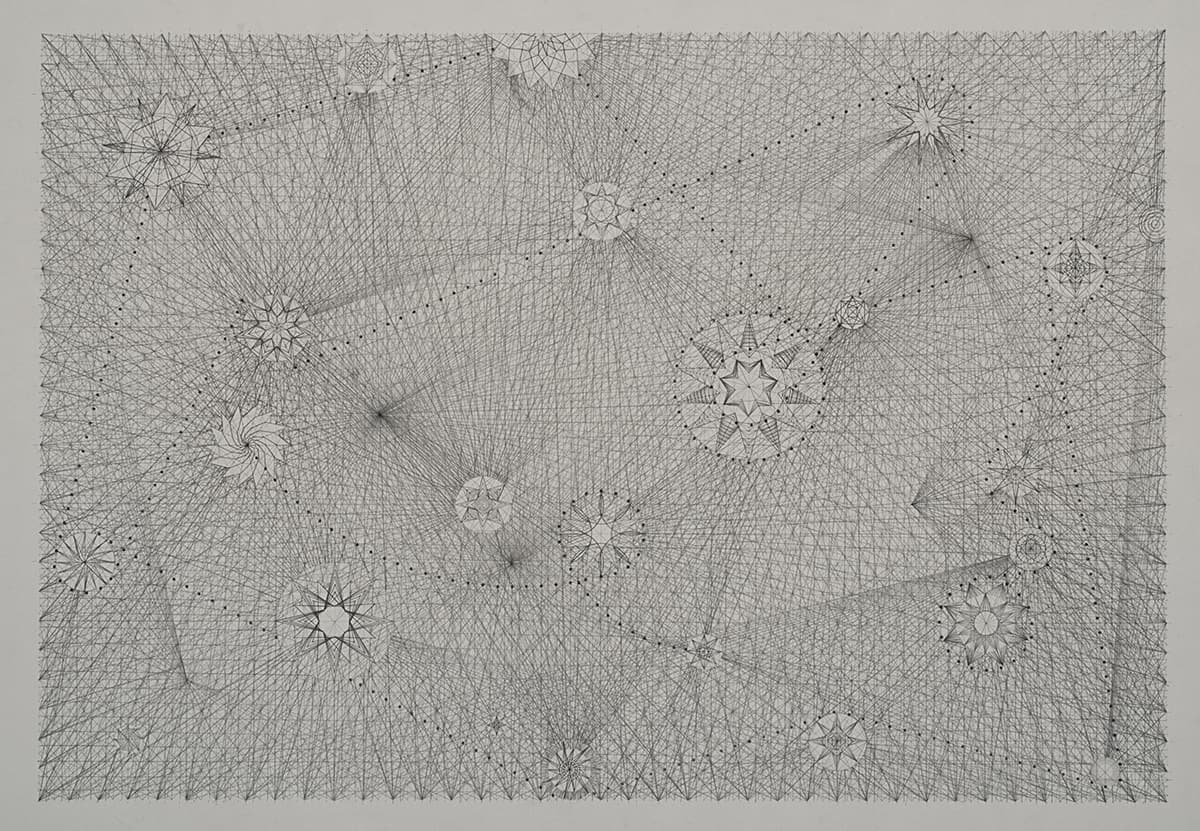

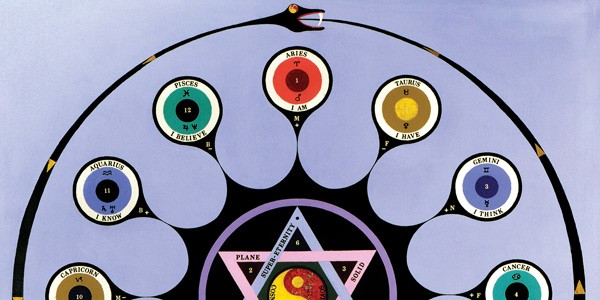

- Cosmos: This gallery “exhibits the ways in which artists try to make sense of the world, while simultaneously attempting to transcend it.”

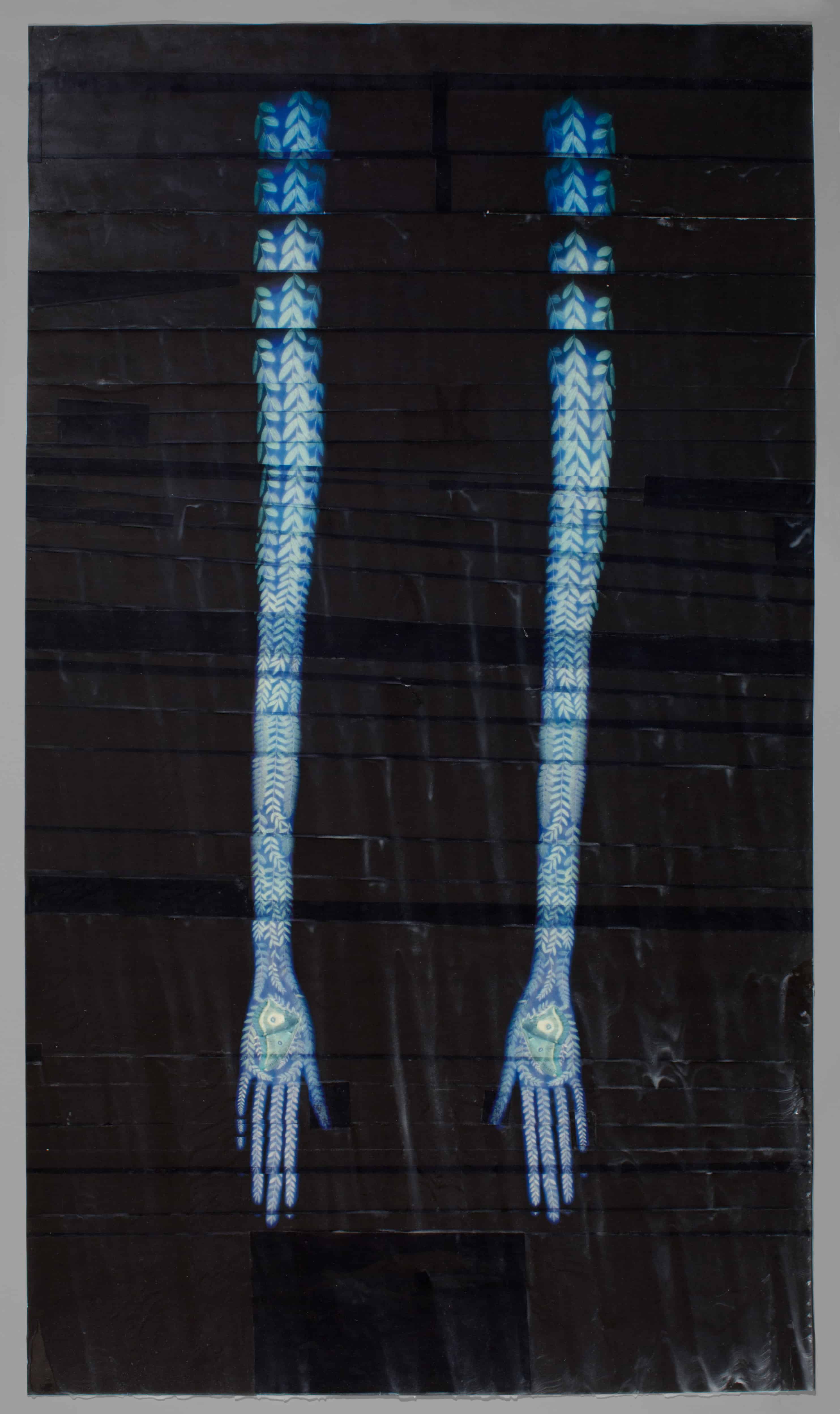

- Spirits: These artists “are unified by an urge to examine concepts of belief and devotion through imagery.”

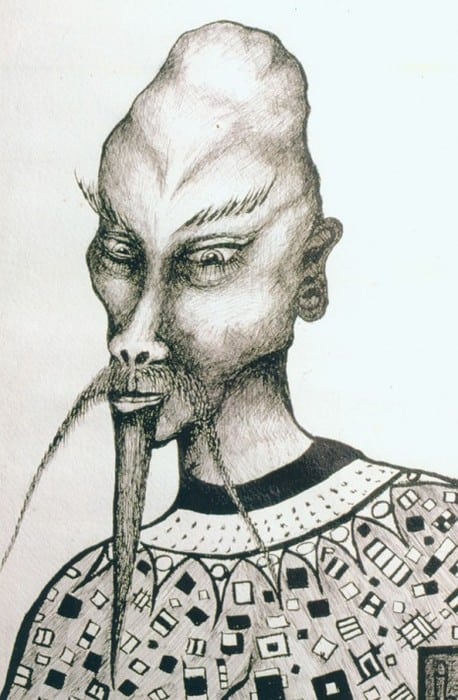

- Practitioners: The works in this gallery are devoted to representations of — or pieces by artists who self-identified as — magicians, witches or seers.

- Altar: “This space is an example of art as a ceremonial gesture, and links us to those who are no longer on the physical plane.”

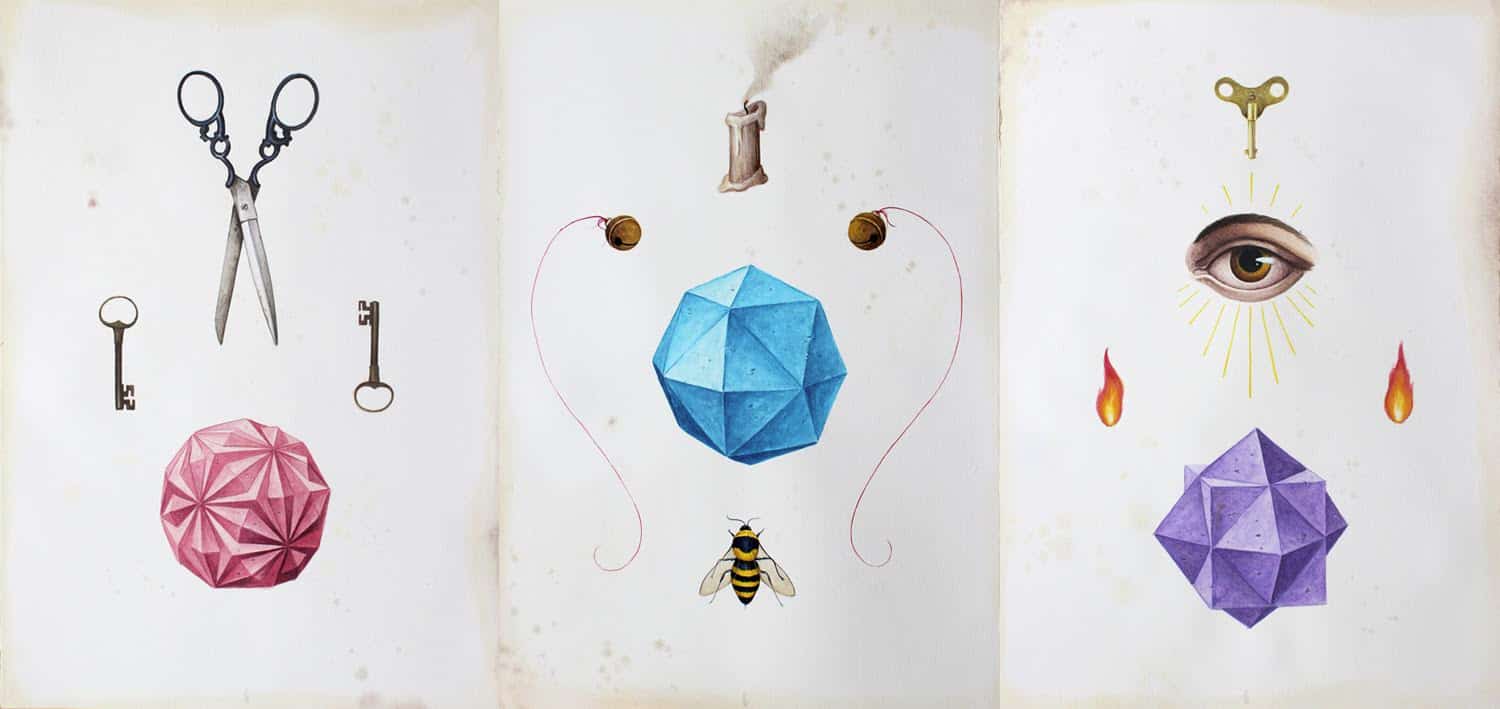

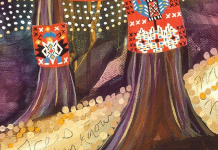

- Spells: The final gallery “shows artists’ various endeavors to catalyze magical action through their creations.”

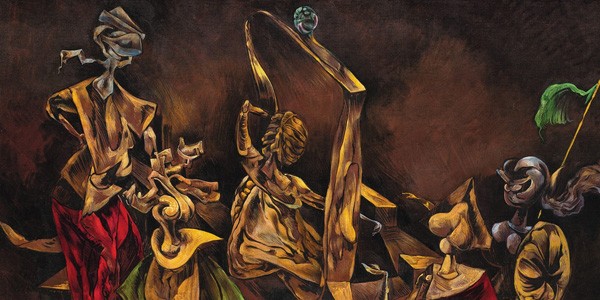

Grossman’s curatorial vision is global, including works by artists from Canada (Scott Treleaven), Mexico (Leonora Carrington), Argentina (Xul Solar, Leonor Fini), Brazil (Darcilio Lima), Switzerland (Kurt Seligmann), Italy (El Gato Chimney), and Australia (Rosaleen Norton, Robert Buratti, Barry William Hale), among others.

The exhibit also honors Greenwich Village’s reputation as a bohemian and artistic epicenter by featuring an array of local visionaries. Moderns like Harry Smith, Peter Lamborn Wilson, Lionel Ziprin and Ira Cohen are represented, alongside a host of contemporary artists including Carol Bove, Jesse Bransford, Helen Rebekah Garber, Jonah Groeneboer, Adela Leibowitz, Micki Pellerano, Max Razdow, and Shannon Taggart.

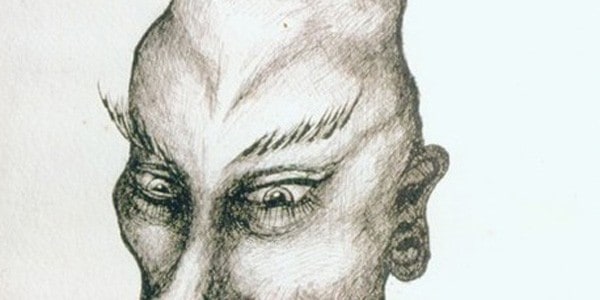

Significantly, Language of the Birds also marks the return of Edwardian bad-boy Aleister Crowley to a Village gallery. Back in 1919, his “trance portraits” captured the attention of the art community and press, and he exhibited that year in the Liberal Club… until his controversial May Morn prompted an early cancellation of the show. Crowley’s return to the Village 97 years later features his idealized self-portrait Kwaw from 1935.

Crowley’s influence in occult circles is evidenced in the oldest works displayed in Language of Birds, as their artists were all one-time students of his. Two pieces by J.F.C. Fuller in pencil, ink, watercolour, and metallic ink illustrate the British military strategist’s painstaking attention to detail. Argentinian artist Xul Solar’s guache painting IAO (1923) is titled after a Golden Dawn magical formula representing Isis-Apophis-Osiris, or birth, death, and resurrection (Iao is an early Greek transliteration of Yahweh). Finally, an untitled pencil work from Austin Osman Spare’s Book of Ugly Ecstasy notebook (ca. 1924) rounds out the oldest pieces on display. Both Spare and Fuller contributed to The Equinox journal in 1909, and a dozen years later — after both of them had left Crowley’s circle — Fuller contributed an article on “The Black Arts” to Spare’s art journal, Form (1921).

I was personally delighted to see Rosaleen Norton, Sydney’s “Witch of Kings Cross,” represented here. Frequently featuring sexualized mythical and occult entities with a striking resemblance to the artist, her work pushed the boundaries of Australia’s conservative restrictions around occultism, religion, and sexual expression. In 1949, police confiscated pieces from one of her exhibitions and charged her with obscenity; a few years later, the courts deemed The Art of Rosaleen Norton (1952), her collaboration with poet Gavin Greensleeves, to be obscene: two images had to be removed from all copies sold in Australia, while in the U.S. copies were destroyed outright. It was wonderful to see her daring and uniqueness celebrated with the striking display of Lucifer & the Goat of Mendes (ca. 1960).

The raids and closings of exhibitions by Crowley and Norton remind us that the kind of art constituting Language of the Birds was at one time marginalized, shunned, driven underground, and even banned. Occult art nevertheless spread in acceptability and popularity, and Grossman’s exhibition includes over a dozen works created as recently as 2015, and even two new pieces dated 2016: Jesse Bransford’s Circle to the Four Corners/Elements (for K.S.), which includes Rebecca Salmon’s brand-new sculpture Mandroglorie. Tonight, people are lined up on a cold winter night to be among the first to see this impressive selection of visionary occult works. This is indeed a cause for celebration.

80WSE Gallery is located on 80 Washington Square East, literally across the street from the east end of Washington Square Park in Manhattan. Hours are 10:30 am – 6:00 pm Tuesday-Saturday. The show runs 12 January 12 through 13 February 2016. For more information, including special events in conjunction with the exhibition, see languageofthebirds.org.