Warning: This piece contains spoilers for the film The Babadook, including its ending.

The Babadook was one of the surprise movie hits of 2014. This ultra-low-budget Australian horror film came out of nowhere to grab the attention of genre-lovers and general movie-goers alike, even leading to a popular call for its lead actress Essie Davis to get a Best Actress Oscar nomination. (She was sadly unable to qualify due to the film having been released on video on demand at the same time as its theatrical release.)

The Babadook is about a widowed mother, Amelia (Davis) trying to raise her hyper-active, conjuring- and gadget-obsessed son Samuel (Noah Wiseman, aged six at the time of filming). Stressed and sleep-deprived, Amelia starts to think that the monster from a mysteriously-appearing children’s book, the titular Babadook, may not only be real but could also be attacking, or possibly possessing, her son.

From the start of the film, it is clear that Amelia is on edge: for a former children’s author to discover a classically-formatted illustrated book – though perhaps a little nastier than usual – in her house, which reappears every time she throws it away or destroys it, could be seen as a manifestation of the loss of both her husband and her career. Anyone familiar with stress and sleep-deprivation knows how the shadows and the images in the corner of the eye can twist, be reformed to fit the worst parts of their imagination… and the film keeps the possibility that we’re just seeing Amelia’s breakdown from the inside. Like so much magick it occupies the liminal, the maybe-spaces where perception and reality bleed into each other.

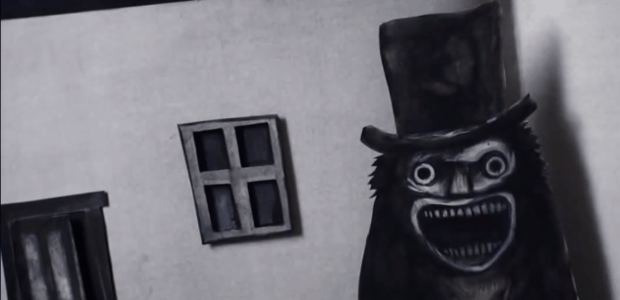

The Babadook itself is, as was once said about the Slenderman, “a very satisfactory booger-man, pressing all the right buttons.” Its shadowy form, sinister grin and cartoony horror aspect draw on all the monsters that lurk in childhood’s open closets and spaces beneath beds. As the lines from the book have it:

If it’s in a word, or if it’s in a book

you can’t get rid of the Babadook.

He wears a hat

he’s tall and black

but that’s how they describe him in his book.

A rumbling sound, than three sharp knocks

you better run, or he’ll hold you in his locks.

ba-ba-ba-dook-dook-dook…

Your closet opens

and you’re honestly hopin’

that he won’t hear a sound

but that’s when you know that he’s around.

It’s also strongly implied that, if Amelia didn’t simply project the Babadook as an external manifestation of her crumbling sense of both self and reality, Samuel created it as a manifested thought-form: that he is learning to control his powers through his obsession with his father’s stage conjuring kit into a very literal kind of magick.

Before the end, it is clear that something is directly affecting Amelia and Samuel; both are temporarily possessed by an inhaled dark cloud which brings out their worst aspects – and it’s only through their love, and Amelia’s mother-bear righteous rage, that the Babadook is dealt with.

The film is unusual in many ways: aside from its tiny budget and Australian location, it stands out with its focus on a mother and son, and by having a woman (Jennifer Kent, a production veteran of Lars von Trier’s films) as the first time writer-director. But for me, the most extraordinary thing about this film, especially as a horror movie, is that it defies convention by having an ending which is non-zero-sum.

“Zero-sum” is a term from game theory. Broadly, it describes a situation where the only possible result of conflict is that one side wins, and the other loses. (It’s zero-sum because if you state mathematically that the winner is +1 and the loser is -1, the sum of the two results is zero.)

The majority of action, suspense, and especially horror films follow this format: there is a clear winner and a clear loser. Horror as a genre has more of a tendency than most for that endgame to not necessarily favour the protagonist — often, the supposed hero doesn’t win.

But, in The Babadook, something else happens…

In the final showdown between Amelia and the Babadook, rather than either of them winning, a compromise is found. Neither defeats the other; at the very end, we’re shown the household has found a peaceful balance. Amelia and Samuel get to live their lives safely, with the Babadook held in their basement — not exactly a prisoner — but safely contained, fed, and treated as kindly as possible.

This kind of non-zero-sum ending is astonishingly rare. When I first saw the film, the thought that stayed with me about it was a quote from Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles:

We’re trying to pull off a track that’ll result in everyone getting exactly the kind of world they want. Everyone including the Enemy.

We live in increasingly dualistic times. From the clash of civilisations between Muslim extremists and the Christian West, to the polarisation of national party politics in most (if not all) nations, the majority of modern narratives in all media, fact or fiction, are us-or-them, friend-or-foe, win-or-lose, right-or-wrong. I think it’s vitally important to dismiss these as not just over-simplified ways to describe a complex world, but actually dangerous to us all. If we’re to survive such tumultuous times, we have to find ways for differing, even opposing viewpoints to co-exist. We need to look for non-zero-sum solutions.

And, we dearly need stories and myths which show this is possible. The Babadook is one such tale. Which ones have you found?