We all float down here

When I think about death, I think about floating. I’ve had vivid dreams for years about dying. The dream is always the same: I’m sitting on a raft, floating down a stream. The water and sky share the same colour: a blurred mixture of magenta and hot pink that looks just like the cover to My Bloody Valentine’s “Loveless,” my favourite album. The water is brightly coloured and thick, like I’m surging forward on a vibrating pool of melting lipstick, my raft propelled by the liquid velocity of a million dissolving Nagel prints. All around me little black leaves, like flecks of impurities on pink diamonds, float by as we drift down the river. The sound of a waterfall ahead, hissing like feedback; the raft sails over the frothing edge and then- nothing. I’m floating in the dark until I wake up.

As you can probably imagine, based on my recurring flirting with the bardo dreams, the idea of floating in darkness triggers some morbidly seductive associations for me. When I first read about the practice of floating in sensory deprivation tanks in Anthony Alvarado’s “D.I.Y. Magick” column in Arthur Magazine, it made me think about my dreams… but it also set off my occultnik alarm bells. Floating silently in the dark, alone, in a pod full of water that’s so heavily saturated with Epsom salt it keeps your body buoyant at all times — you could do some interesting stuff in that state.

The floating pioneer

Before embarking on my first float, I did some homework by reading the work of float pioneer Dr. John C. Lilly. A fascinating scientist (whose theories proved to be very influential on “alternative” thinkers like Timothy Leary, Robert Anton Wilson, and Antero Alli), he researched sensory deprivation as a way to disprove the thinking of behaviourism.1 In the behaviourist model, the human mind is a purely Pavlovian machine.2 It reacts to stimuli; left to its own devices, without any external stimuli to kick it to life, it would be inert. If human consciousness was a car, stimuli was the ignition key and gas that kept its motor running.

Lilly challenged this theory by putting people in his sensory deprivation tanks. If the behaviourists were right, their minds would just shut off. But on the contrary, Lily and his many deprivation subjects found the opposite to be true — their minds didn’t shut down, but expanded. Rather than fall asleep, their minds seemed to awaken and go to places that weren’t accessible to them when they were being bombarded with stimuli. Subjects in the tanks reported hallucinations, dreams, and all sorts of other sensations and experiences completely at odds with the Pavlovian model.3

Lilly ran experiments with the sensory deprivation pod for years, as well as doing work to study the possibility of interspecies communication between humans, dolphins, and whales.4. He also wrote lucidly about synchronicities, and his theories on how to influence and induce personal change became deeply influential in the psychedelic and occult communities.5 The entire “Eight-Circuit Model of Consciousness” — conceived of by Leary, and later expanded by Robert Anton Wilson and Alli — would be impossible to conceive of without Lilly’s groundbreaking work.

Entering the space egg

Having read all that, the thought of seeing crazy shit and inducing change within myself was so tempting that it overwhelmed whatever death-dread the idea of floating conjured up in me, and I committed to doing it. I found a company in Arizona called True REST that has flotation pods available to the public for one-hour “float spa” sessions.

The first time I floated there, I was escorted to my room after watching a safety video. The video assured first time floaters that they wouldn’t drown, and also emphasized that any discharges of bodily fluids in the tanks would incur a heavy penalty fee. As I watched the video, I saw a Falun Gong poster on the wall. A bald monk meditated in front of a bubble; suspended in the bubble’s centre was a swastika. I had to keep reminding myself that swastikas weren’t always totems of genocide so the poster wouldn’t seem like an ill omen.6

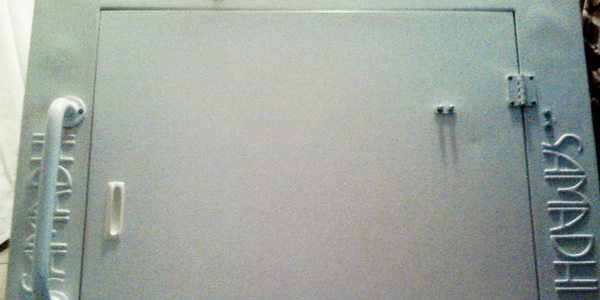

When I was shown to my room, I got my first look at the pod. The sensory deprivation chamber looked like a giant space egg. I was half-expecting Kubrick’s Starchild to emerge as I popped open the lid, wiping the salt out of its cosmic eyes. Lying naked in the water, synth-based new age music chimed softly in the pod for a few minutes before shutting off. I floated in the dark for an hour.

I can’t say that the first time I floated was a revelatory experience. If anything, the best advice I can give anyone who hasn’t done this is to not expect any kind of metaphysical fireworks the first time through. It takes some getting used to. The water is so heavily salted that it stings like hell if it gets in your eyes or in any skin abrasions. Getting comfortable floating in the confined space can take some time as well. Like doing psychedelics for the first time, it’s easy to get hung up on all the logistics and weirdness of being introduced to a new state of being that you miss out on the chance to go deeper into it.

Going further down the river

I did leave my first float feeling immensely relaxed and refreshed. Jerry Rubin, one of Dr. John Lilly’s floating subjects, summed up his first deprivation session by saying “I felt the whole experience washing my brain clean.”7 I felt the same way. Returning for future floats, I began to experience some of the higher weirdness Lilly’s other subjects reported.

I saw flashes and arcs of light blooming in the darkness of the pod. The impression of hands and ghostly faces forming and dissolving around me. In one session, I drew a sigil on my belly before getting into the pod. I tried to use the silence of the pod to focus on doing a ritual working, drowning my monkey mind in the salt water so I could be clearheaded enough to throw my intention out into the universe. Blue lines crackled overhead and coalesced into the shape of an eye, which stared at me unblinking for the rest of my float. I was so startled by its appearance that I forgot what my sigil looked like or even what I was trying to accomplish in the first place; the watcher remained, though, looking like an Eye of Horus lit up in neon blue. It didn’t feel like a hostile presence, but its stare felt invasive nevertheless. I felt like that huge pupil was peering at something beneath my skin. It gazed down at my floating body until the pod started playing its gentle “wake up” music. The cerulean eye blinked, vanishing into the black.

It isn’t just that you see things while you’re in the pod; your ability to feel the space you’re in radically changes. While most float pods are relatively small, enclosed spaces, they feel huge in the dark. Even though the walls of the pod were easily within reach, they felt like they were miles away in the silent darkness. Floating in the pod feels like floating in the immensity of space, like you’re a speck of stardust drifting through a void that stretches on for billions and billions of light-years.

And without the anchors of a physical space or even your own body to keep you grounded, time itself starts to feel insubstantial and meaningless in the float. “No difference between minutes and millions of years,” Stanislav Grof used to say about time dilation.8 I’ve had floats that seem to go by in minutes and ones that seem to drag on for hours and hours. Floating in the pod, sometimes I wonder if this is what death is like, if the afterlife is just floating in black for the rest of eternity, feeling your memories trickle out of your head like the salt dripping off my hands when I raise them out of the water. Peaceful, relaxed, and quiet.

Floating on the inside

Having floated eight times so far, I’ve found the flotation pod to be a great tool for meditation and exploring inner space. The almost-immediate relaxation it induces smooths over the resistance I normally feel while doing a seated meditation. Meditating on dry land, it becomes easy to focus on the room you’re in. The sensation of the floor digging into your ass, the ambient noises the room makes, the constant feeling of separation between you and your environment. Here’s my body, and there’s everything else. Meditate deep enough and these can all be overcome, of course. The difference is, in the flotation pod, there is no ambient noise to distract. There’s no floor or cushion beneath you, and the lukewarm water makes it so it becomes hard to feel your body after a few minutes. That thin pencil line in your head that separates you from everything, that sets skin and bones apart from surroundings, gets blurred by the eraser drag of the float pod. It becomes easy to forget yourself quickly in there, allowing your brain to blast off to No-Mind in no time.

Floating helps achieve a kind of “soft reset.” It’s that state of clarity that can be achieved during ecstatic or traumatic states, that moment of crisis where your mind dumps all its baggage and actually opens itself up to change. Lilly described the brain as a biocomputer, and sensory deprivation as one of the ways (along with sex, drugs, physical exertion, trauma, and trance states) to make that computer “reboot.”9 As above, so below: Just as entire nations can dramatically change themselves during times of crisis, so can the individual reshape themselves when their “biocomputer” gets overloaded with stimuli and stress.

Being able to still your mind and focus is essential to any practice, be it creative or magical in nature. While the float pod is no substitute for developing a disciplined practice of concentration and meditation outside the pod, it can create conditions that let you skip ahead and “get to the good stuff” quicker when you need to work in a time crunch. And while it’s not as powerful a head-fucker as a strong dose of hallucinogens, it is a great way to cheaply (and legally) derange your senses for a bit.

Turn off your mind, relax, and float

If it had been a few decades ago, being able to have this experience for yourself would have been a little more tricky. Thankfully you don’t have to go all the way to Esalen or be part of a research control group anymore to float on the river of night’s dreaming; float spas like True REST are popping up all over the place. Most of these places don’t offer the marathon, multi-hour sessions that Lily and his subjects participated in, but for the price of a massage you can experience an hour of weightlessness that will help you shed the pressing gravity of your day.

While most of these places aren’t afraid to pay tribute to float pioneers like Lily and Michael Hutchinson, they also take care to emphasize floating’s relaxing and therapeutic applications over its psychonaut roots. Much in the same way that yoga, once an ancient system of metaphysical techniques and worldviews, has become repackaged as a thing that soccer moms can do to tighten up their tummy tucks and get more bendy.

It’s like The Beatles sang: “Turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream / it is not dying, it is not dying.” Floating isn’t dying, but sometimes it feels like a rehearsal for it. As the old saying goes: knowledge is power. For any magician looking to grow their power, the kind of knowledge floating has to offer shouldn’t be ignored. We all need to log some training hours with the infinite. Even if it does burn your eyes.

Here’s a couple of resources you can use to find a place near you where you can float:

- where-to-float.com

- floatationlocations.com/where-to-float/

Image credits: Richard Ling, Ulleskelf, and jm3 on Flickr

- Marshall Hammond, “The Unlimited Mind of Doctor John C. Lilly,” Reality Sandwich. [↩]

- Dr. John C. Lilly, Center of the Cyclone: An Autobiography of Inner Space by Dr. John C. Lilly (Float On, 2017). [↩]

- Dr. John C. Lilly, The Deep Self: Consciousness Exploration in the Isolation Tank (Penn Valley, CA: Gateways Books & Tapes, 2006). [↩]

- Dr. John C. Lilly, Lilly on Dolphins (New York: Anchor Press, 1975 [↩]

- DJB, “From Here to Alternity and Beyond with John C. Lilly,” Mavericks of the Mind. [↩]

- See Donyae Coles’ “Reclamation after cultural appropriation.” [↩]

- Dr. John C. Lilly, The Deep Self: Consciousness Exploration in the Isolation Tank (Penn Valley, CA: Gateways Books & Tapes, 2006). [↩]

- Dr. John C. Lilly, The Deep Self: Consciousness Exploration in the Isolation Tank (Penn Valley, CA: Gateways Books & Tapes, 2006). [↩]

- John C. Lilly, Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer (Float On, 2014). [↩]